Princess Alia Al-Senussi is a key figure in the development of cultural relationships between the West and the Global South, and in the growth of the art scene in Saudi Arabia. In a conversation moderated by LUX’s Leaders and Philanthropists Editor, Samantha Welsh, Alia Al-Senussi speaks with South Asian philanthropist and collector Durjoy Rahman about significant art world debates and developments at the nexus of the developed and developing worlds.

Baku: Durjoy, is the relationship between art in the Global South and the rest of the world changing?

Durjoy Rahman: I have been collecting for the over 25 years, and I have always been passionate about creativity, both personally and professionally. Living in Dhaka, I have realised there is a lot of untapped creativity that can probably be moulded and presented to a wider audience, to increase visibility, benefitting Bangladesh, South Asia and, in a bigger picture, the Global South.

These days there is a very fashionable phrase: “Your West is my East”. What one person calls “West” is actually somebody else’s “East”. It depends on the position you are coming from. I have asked many scholars, and no one has been able to give me a clear definition of what the “Global South” is. I think the geopolitical or geographical definition has different meanings and narratives and I expect plenty of discourse and redefinition during the next decade.

Baku: Alia, what has your global vision of the art world been informed by?

Alia Al-Senussi: I came to the art world from a very established position, in the heart of London, so my view has been shaped by the Western perspective, an institutional perspective, a gallery art world ecosystem perspective.

I was very lucky to enter the art world at a time when these perspectives were changing. Tate Modern had just opened and revolutionised the way that we put art in context. There is no longer the “South Asian gallery”, the “Middle Eastern gallery” or the “Asian gallery”.

Alia Al-Senussi in AlUla, Saudi Arabia. She is a Senior Advisor, Arts, and Culture, to the Ministry of Culture in Riyadh

It was about showing art in conversation with itself, through the eyes of a subject, subject matter, or a generational perspective, rather than a geographical one. And, ever since, as much as I’m in the art world, my perspective on the art world is not as an art historian. It is very much about somebody looking at art, strategy and cultural strategy through the perspective of cultural diplomacy, soft power and how culture interacts with the art world ecosystem, but also very much with identities, governments and politics.

Baku: Alia, how have you noticed the art world changing in the Middle East?

AAS: My work in the Middle East started in 2007, when Art Dubai started. In the last five years, we’ve seen a rapid evolution in the Middle East, positive developments in Saudi Arabia, and Dubai becoming, in many ways, a platform for art from the Global South.

Baku: What do you think is the role of philanthropy in art. Does it engage, facilitate and shape discourse?

DR: This is what DBF is all about. From day one our approach has been very discursive, and we try to position our strategies in a very discursive manner.

For example, we work with photographers like Sunil Gupta, whose retrospective involved queer art. On the other side of the coin, we work with Wadham College of Oxford University, restoring the Holy Qurans, which we announced during the month of Ramadan.

My philosophy towards philanthropic activities and my involvement in the foundation is to challenge negative perceptions. It’s not only about Bangladesh, but the whole perception of South Asia, that I am trying to change through the activities that DBF undertakes. This is why we don’t only focus our activities in Southeast Asia but globally, be it in Europe or America.

Baku: Alia, could you share with us your belief about the role of art and philanthropy?

ASS: I think it is at the very heart of changing perception. I have a deep belief in – as Durjoy said – the power of culture to change people’s minds and perceptions. And I’m not just talking about the West, I mean: it’s even neighbour to neighbour.

For example, we’ve seen black art in the United States transform people’s perceptions of BLM and people’s perceptions of segregationist history. You walk around the Tate galleries, and you see two paintings facing each other in the room about conflict and war. One is about the pogroms in Eastern Europe, and one is about the massacres at Sabra and Shatila [of Palestinian refugees by Christian militias during the Lebanese Civil War in 1982]. These speak to exactly the same universal horrors that many people experience but are from two very different conflicts and parts of the world.

Alia, what responsibility or soft power do you feel you have?

I feel a deep sense of personal and professional responsibility. In any projects that I get involved in or commit to, I pay a lot of attention to professionalism. I teach a lot and one of the questions I often get asked is, “How do I get involved in the art world? How do I start my career?” I say, “Get involved, show up.”

I think the idea of showing up is really important. Someone invites you to something, go. Someone expects you to be at something, be there. Someone expects you to respond to your emails, respond; and I think that idea of showing up really illustrates a commitment to people.

Baku: What is soft power for you, Durjoy? How can you and/or art bridge discourse?

DR: Everybody wants to understand art. Even Picasso said, “Everyone wants to understand art. Why not try to understand the songs of a bird?”

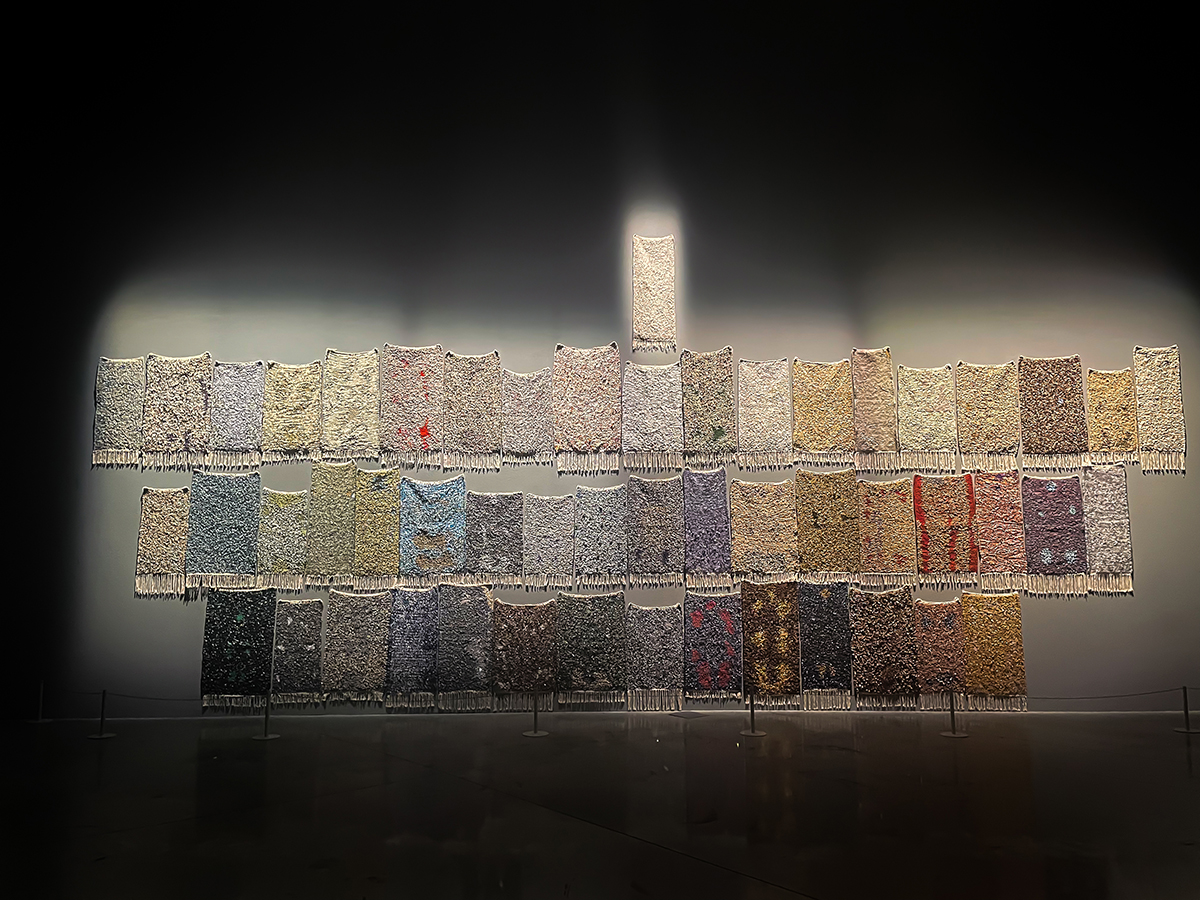

An artwork from the Bhumi project, supported by the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation that was shown at the Kochi Biennale in India in 2022/23

When I invite people to an art show and they say that “Well, we don’t understand art.” I say, “There is nothing to understand. Just be there. Just try to comprehend that it is something interesting.” An example of how it’s not about soft power, but engagement, is what DBF did during the pandemic. All the major art institutions in South Asia closed for either health or commercial reasons. DBF decided to get involved with a community from north Bangladesh, which had hardly been hit by COVID-19. The project was called Bhumi and involved a minority group in the area who were craftspeople working in textiles. The project involved 260 people from 60 families, and it supported their daily livelihood. The project didn’t end with the pandemic, it was actually taken to last year’s Kochi Biennale to exhibit the works of the craftsmen and shows what is possible during difficult times.

This is an example of how art, philanthropy and art activism can show how culture can play an important role in times of crisis.

AAS: Just like Durjoy said, you see these very different and very nimble organisations involving themselves with communities and making a difference. The Islamic Biennale did exactly that. It was really revolutionary in the context of art in Saudi Arabia. The Islamic Arts Biennale was at the Hajj terminal in Jeddah, and offered locals to come to a place that they’d never entered because the Hajj terminal inherently is a place for Non-Saudis to come into Jeddah to then go on Hajj.

The locals could see this exceptional building, feel the power of Islam, but also of spirituality and of a community coming together. For people who were not Muslim, or had no connection to the Hajj, they saw objects and works of art in a contemporary and historical environment.

Certain organisations have the power to be really nimble. They can profess their politics and support artists for art and culture. I think Delfina Foundation, for example, has been very clear about their support for artists from across a plethora of humanity and does it in a sophisticated, nuanced, and empathetic manner.

Baku: Where are you seeing Next Gen concerns amplified through art?

AAS: I think you see the next generation wanting to amplify diverse voices. There is this desire that art is geographically, ethnically, and sexually diverse so people can express the totality of who they are. There is a sense of activism to it, but there’s also a sense of declaration. I don’t always read into these institutional shows or works of art as activism. Sometimes an artist just wants to say, “This is who I am, and this is the art I make.” Artists are going to make art based on their life experiences.

Baku: Durjoy, where do you think the line is between declaration and activism?

DR: I think the majority of people want to see the origin of the artist, their background and their surroundings, reflected in the work they are producing. If I show a Bangladeshi artist and his or her work looks too different or has no context, sometimes curators even question it and say it doesn’t show their struggle or their originality. I’m not an art scholar or academic: I look at art based on whether I like it. But I think it’s important for an artist or a creative practitioner to show the origin, the struggle, and the history.

I think that we want to encourage artists going forwards to show their origin and their perception. An artist should be free to express their opinion, whether they are from Iraq, Lebanon or Africa. If they are willing to they should go ahead. DBF and I always try to work with artists who have enormous creative boundaries that they want to exhibit in front of their audience.

Al-Senussi in conversation with installation and media artist Chris Cheung during Art Basel in Hong Kong

Baku: To what extent do Next Gens feel obligated to witness and pivot or create change?

AAS: What I see more in my lecturing and my academic experiences, is that the next gen is very much about wanting to change the world and wanting to illustrate that. Through their careers and artwork, they want to be a part of the change in some way. It’s a little disheartening because there is this negative feeling about the future of the world, but at the same time there is a feeling that maybe we, collectively, can change the world.

You also see artists that are just reflecting on their own childhoods, like Farah Al Qasimi. She talks about her family home and the changes shifting in the UAE. It’s an activism, but then it’s also a reflection on the changing world.

Baku: Can art collaboration bring about changes of perception?

DR: Definitely. Art has a vital influence on culture towards current situations. I think art has a very influential way to foster international connections and collaborations and can question issues that are happening.

Read more: Maria Sukkar and Durjoy Rahman on supporting artists from your hometown

When I was in Paris at Asia Now art fair, I was talking to an artist from Israel and an artist from Jordan. When these two artists sat together, they realised where the problem lies. I didn’t see a division in their opinion, and I think this is an example of art bridging divides. Art can be used as a very strong tool to solve many of our problems including sustainability and global climate change.

AAS: I think art, at this time, is one of the only tools that we can look to, to unite us or to heal us. Unfortunately, it can also be used and utilised in other ways, but I have faith and hope that we will see a change.

Online Editor: Isabel Phillips