Through her astonishing photographs, the Moroccan artist Lalla Essaydi gives voice to both herself and the women she depicts, says Charlie Burton

On Lalla Essaydi’s 16th birthday she got into trouble. It was 1972 and, back then, Marrakech, where she was growing up, was one of Morocco’s most conservative Islamic cities. That night, her brother suggested they go out to a local club. She knew it was risky. “So we did it in such a way that we thought nobody else knew,” Essaydi recalls. Inevitably, her parents found out. As punishment they grounded her for two days alone inside a beautiful, empty old house that once belonged to her grandfather. The reasoning was that, while alone, she would realize the severity of what she had done.

Instead, it just made her angry. “Of course, for my brother – nothing happened to him.” She felt it wasn’t fair, yet it was typical of her experience of that country in which girls were expected to behave differently to boys – they weren’t allowed to see friends by themselves, they were not allowed to be ambitious or independent. “In the household itself, everything was catered to my brothers,” she says. If the men wanted a drink, she would have to fetch it.

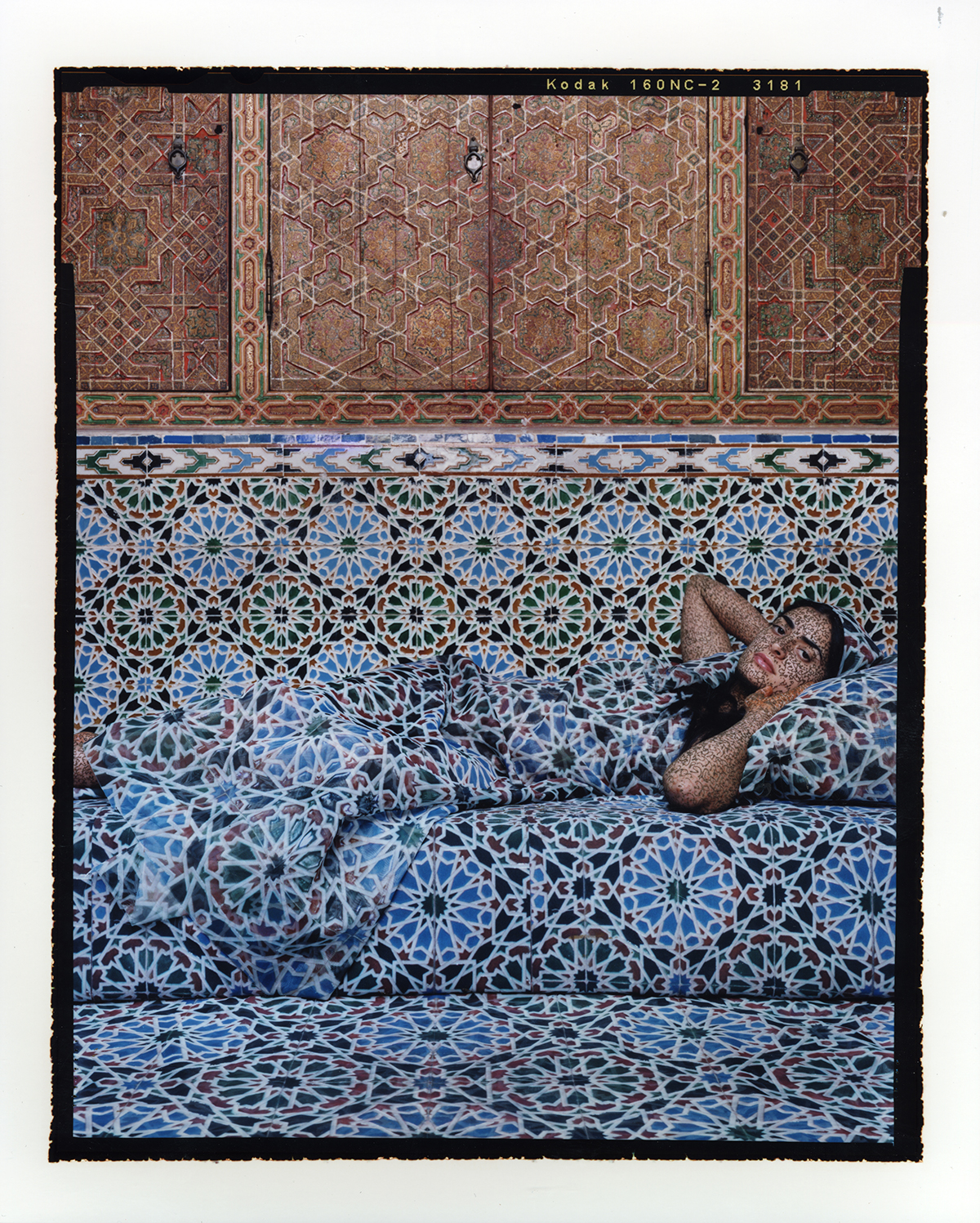

Today, Essaydi works as an artist, dividing her time between New York, Boston and Marrakech. She has worked in various mediums, including painting and video, but today she is best known for her series of photographs including Converging Territories, Les Femmes du Maroc, Harem and Bullets. These series, rooted in her childhood and teenage frustrations, offer a sophisticated and intricately beautiful expression of her personal view of women in Islamic society. Essaydi’s subjects are women in Middle Eastern dress, staring – provocatively, or perhaps simply with a cool self-assurance – out of the picture at the viewer, and the structure and composition of these works make them more like paintings than documentary photographs.

Often Essaydi will split the images into diptychs and triptychs, and in the compositions in all but her first series, Converging Territories (2003–04), the women are posed like figures in so-called Orientalist paintings – a genre of painting associated with Middle Eastern and North African subject matter that became fashionable during the 19th century, especially in the work of French artists.

However, Essaydi’s photographs do not simply imitate these historical works; rather she subtly subverts the Romantic exoticism and fantasies characteristic of this genre. Perhaps the woman’s feet are dirty, or the decorative background is made out of bullets – with details such as these, Essaydi debunks the idealization of the ‘Orient’ by European art and reveals the profound mismatch between art and reality. For most of her photographs, too, she covers her subjects’ bodies and scenery with Arabic calligraphy written in henna. Unlike the women in the paintings of the French Orientalist Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), one of her major reference points, Essaydi’s subjects have been given a new voice through this text, even if the writing is not always legible.

There’s a possible life where Essaydi would never have achieved so much. Had she stayed in Morocco, she says, she would not have developed the feminist ideas crucial to her work. Her parents sent her to high school in Paris, and in 1977 she moved to Saudi Arabia. “Growing up in our culture, we were very sheltered,” she explains. “So it was when traveling that I started really thinking of independence – that I am an individual. That created such a difference between me and my siblings, especially my sisters, in the sense that I can’t be easily brainwashed,” she says. “Even now it’s strange how, as soon as I go to Morocco, I start to think differently – and that worries me. As soon as that starts happening, I just leave.” Think differently how? “If I walk in the streets of Morocco, I can wear a pair of jeans and a T-shirt exactly like I do in the States, or in Europe. But I don’t feel comfortable about it.”

She had two children while living in Saudi, but Essaydi eventually decided to leave for Boston in 1996 so they could be educated in America. There, she enrolled at art school. One day in 2001, during the second year of her master’s degree, the curator of a nearby museum came to look at some of Essaydi’s photographs. But instead she found herself captivated by a huge painting that Essaydi had almost finished: a deconstructed version of Gérôme’s The Slave Market. She asked what it was about, and Essaydi explained how it was her twist on a work of Western imagination. “But I thought it was real,” said the curator. Like many of Gérôme’s contemporaries, this woman assumed the original was documentary. “I was shocked,” recalls Essaydi. “If a person specializing in art, and with a PhD, can still think it was real, I knew that I had to do something about it.” Having alighted on her style and calling, she knew it would cause a rift between her and her family.

Depictions of women, particularly in public spaces, ran against her culture’s traditions. “And our religion, too, arguably,” says Essaydi. “I didn’t know, also, how my family would feel about my name and, therefore, their name being out there. Somebody from Europe wouldn’t understand how it is and they’re completely crazy about being in the media in the US, but it’s totally the opposite in Morocco.” Her hunch was right. Her relatives forbade her from working at the family house when she visited. “No one talked about my work for a very long time,” she says. “I wasn’t showing in Morocco, and I believe that it’s because of that, they thought what I was doing was wrong. The situation was quite hideous. I was even accused of doing pornography by somebody from my family.”

As Essaydi’s reputation grew, however, their views softened. In any case, her father had been a painter. “When people wrote about my work, and the family started reading about it and found out what I was trying to do, there was some kind of understanding. Now, I actually have a lot of people who like my work in the Middle East and in Morocco.” These days, Essaydi has a studio in Marrakech and is surrounded by supportive relatives.

So after more than a decade working with these ideas, and having won her family’s acceptance, does she feel that she can now move off in a new direction artistically? “I’m changing as the time changes and circumstances around me change – that applies to my work, too. Right now, I think that I really am ready to play. I have images in my head of what I’m trying to accomplish, but so far the results are not exactly as I want,” she says. “So I keep pushing.” .

Photography courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

A version of this story originally appeared in the Spring 2014 issue of Baku magazine.