The Middle East is providing a fertile ground for an increasingly relevant sci-fi scene, as artists and authors engage with themes of rapid socio-economic expansion, futuristic architecture, technological advancement, and a complex political past and present, reports Daniel Miller

“Science fiction is the most important literature in the history of the world, because it’s the history of our civilization birthing itself,” the US novelist Ray Bradbury wrote in 1995. For two centuries after the 20-year-old Mary Shelley published Frankenstein (or The Modern Prometheus) in 1818, first through the space age and then in cyberspace Western science-fiction not only described but anticipated and imagined the world’s future.

Seventeen years after 9/11, a new chapter of the story is being written in the Middle East, with major international agencies and institutions increasingly exploring science fiction-influenced writers and artists from the region. In 2017 Hassan Blasim, a Finland-based expatriate Iraqi, had his short story anthology, Iraq + 100 (a collection of visions from 10 authors of Iraq, 100 years after the 2003 US- and UK-led invasion), published by the UK Arts Council-funded Comma Press. It received widespread coverage. Blasim’s book builds on the success of his compatriot Ahmed Saadawi’s novel Frankenstein in Baghdad (of which there is talk of it being made into a film). Meanwhile, the art world is promoting figures such as the Qatari-American artist and writer Sophia Al-Maria, who, in 2016, opened a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York, and British-Lebanese audio surveillance specialist Lawrence Abu Hamdan, both alumni of London’s hyper-ideological Goldsmiths college.

But the speculative fiction connection with the Middle East goes back further. In 1965 Frank Herbert’s Dune – whose source material is widely cited by this new generation of writers and artists – fused post-war geopolitics with Arab history to rewrite the story of the birth of Islam on the desert planet of Arrakis. Much earlier in history, Cairo-based doctor Ibn Al-Nafis’s 13th-century novel, Theologus Autodidactus, cast Greek alchemical and metaphysical ideas of spontaneous generation and apocalypse into the story of a feral child living in a cave on a deserted island. At the limits of imperial powers, the Middle East remains a crucible of hybridized imagination.

Hamdan and Al-Maria, along with the Brooklyn-based electronic music producer and artist Fatima Al-Qadiri – the Senegal-born daughter of a Kuwaiti diplomat and a Black Lives Matter spokesperson – reflect the genre’s major themes of globalism, post-colonialism, politics, dislocation and complicity, in a world in which science fiction is increasingly merging with reality, or virtual reality. In 2017 Saudi Arabia granted citizenship to the Hong Kong-made humanoid robot Sophia, and Abu Dhabi and Riyadh have released projections of their respective futuristic desert cities Masdar and Neom. And in 2018, as the Arab-American oil giant Aramco prepares for the largest IPO in history, the Middle Eastern syntheses of the future and the present, the alien and the familiar, and the geopolitical and the artificial, seem likely to continue to develop.

Here are six names to know on the 21st-century’s Middle Eastern sci-fi circuit:

Best known for coining the term ‘Gulf Futurism’, Al-Maria told UK website Dazed how “the region… has been hyper-driven into a present made of interior wastelands, municipal masterplans and environmental collapse, thus making it a projection of a global future.” She is also the author of the memoir The Girl Who Fell to Earth (2012).

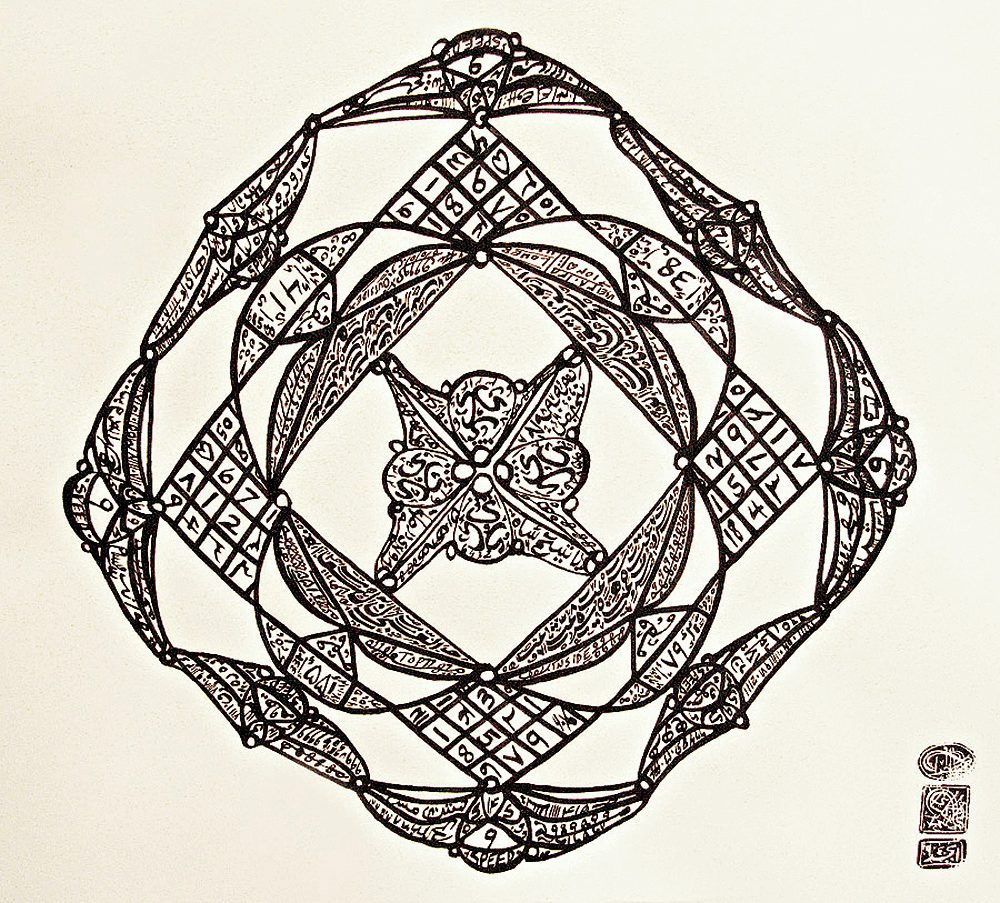

An American textile artist living in Iran, Alvanson combines mathematical complexity with esoteric inspiration in her work. In her 2008 exhibition, entitled Nomad, at Tehran’s Azad Gallery, she presented artefacts, including nine Persian veils, nine drawings influenced by traditional Islamic art, and an animation called Ninefold, to explore the Middle Eastern occult’s embrace of the number nine as “the number of worlds created through the hidden bonds of spells and collective tides.”

A US-based computer scientist, Ahmad is the founder and editor of the website Islam and Science Fiction. Set up in 2005, it’s a hub of English-language resources, essays and interviews on the depiction of Islam and Islamic themes in science fiction literature written by Muslims.

Through her project Sinbad Sci-Fi – which aims to “revive Sindbad’s adventurous spirit for exploration and discovery” – UK-based curator and Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts Yasmin Khan has been hosting events and discussions on Arab science fiction at British institutions and literary festivals since 2013.

In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain (2016) by Larissa Sansour who was a panelist at one of Yasmin Khan’s events (Images courtesy of Larissa Sansour & Soren Lind)

The cult Iranian artist and philosopher Negarestani scored a surprise underground hit with his sui generis novel Cyclonopedia in 2008 – a theory-fiction connecting occultism, numerology and conspiracy in a treatise examining oil as a sentient alien entity, telepathically controlling humanity.

Cyclonopedia complicity with anonymous materials by Reza Negarestani (Images courtesy of Reza Negarestani)

Sansal’s first novel The German Mujahid was the first work of fiction by an Arab writer (Sansal writes in French) to recognize the Holocaust in print; his seventh, 2084: The End of the World, won the French Academy’s Gran Prix for an Orwell-inspired story of the theocratic kingdom of Abistan. His books have been banned in Algeria, where he still lives, because of their criticism of the military government. Sansal, however, continues to challenge expectations, causing uproar across the Arab world for visiting Israel in 2012.

Want more? Visit Art Dubai’s 2018 Global Art Forum for a programme of talks, presentations and discussions themed around the title ‘I am not a robot’, on 21-23 March at venues in Dubai

Main image courtesy of Getty Images. Images courtesy of Harper Perennial, Azad Gallery, Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad, Reza Negarestani, Europa Editions, Larissa Sansour and Soren Lind