The highway from Baku to Balakan arrows through plains, weaves along mountain streams and skirts opulent palaces and oilfields alike. Rob Crossan takes a journey from modern to ancient

The brick minaret looks like a Victorian factory chimney from a Dickens novel; ochre-red in colour and dwarfing everything but the distant mountains. Dusk is enveloping the town of Balakan as we pant and pad up the 125 spiral stairs to the summit.

Rearing up to my left lie the voluminous ranges of the Caucasus Mountains, their gun-metal grey slopes, peaks and gullies barring the way to Russia. Ahead of me, just beyond the cherry-red tin roofs, peeking shyly out above the swathes of nut and chinar trees, lies the Azerbaijani border with Georgia.

“We should leave before the call for evening prayer begins,” whispers Chingiz, my guide, as we slowly descend the tallest minaret in Azerbaijan and enter the adjacent mosque. Layer upon layer of overlapping carpets cover the floor of the squat, oblong building– stripes, swirls and zigzags of cherry-reds, wholemeal-browns and strident purples are illuminated by flared streaks of pale-yellow sunlight, which spill on to the mats. A solitary, barefoot man in a starched white shirt and light-blue jeans kneels down to pray.

This is the far north-west corner of Azerbaijan and the last stop before Georgia on the county’s most beautiful road. It’s more than 500km to Balakan from Baku, the country’s cosmopolitan capital and our starting point three days previously, which was already taking on the hue of a long-sequestered memory…

The revolving restaurant at the top of Baku’s TV Tower, a better-known Azerbaijani summit, feels like a vintage Pullman railway carriage, all overstuffed armchairs and polished china, with waiters who appear to glide on roller skates. My driver, guide and I are enjoying a late-morning feast of hunks of cold salmon, vegetable spring rolls and shrimp, as the Caspian Sea views serenade us from below, before hitting the road. “The Balakan highway was a very important trade road,” Chingiz tells me. “But it’s not used nearly as much these days. It’s a road where, even if you want to, you just can’t rush – the landscape is too beautiful to speed through.”

Leaving Baku behind, the road unfurling in front of us like a black tongue, we watch the urban sprawl simmer then fade to an open landscape of sable-coloured rolling hills, lopsided telegraph poles and dun and chocolate-coloured scrub. Intermittent ashes of sun turn the hillsides shades of gold and tangerine.

About a hour outside Baku we arrive in Maraza, a town where time has slowed down to the speed of the next backgammon game, played by men with neat white moustaches on worn, crinkly faces, who congregate by the sides of the road. Amid the hiss of cicadas, the three of us alight at the Diri Baba Mausoleum, built into a cliff face at the far end of town, adjacent to a 17th-century graveyard full of tombstones decorated with technicoloured handkerchiefs. According to local legend, Diri Baba (which translates to ‘Living Grandfather’) was a mystic whose body, laid to rest here in 1402, did not decompose for 300 years.

Via a crumbling staircase, seemingly taken from a ruined Escher painting, I slowly inch my way up past two tiny stone-floored rooms, bedecked with a morass of rumpled cushions, to the gleaming white-domed roof. I crouch on the cliff edge and watch two white butterflies dance a manic polka around me. The tombstones in the distance, their engravings whittled away by centuries of gusts and gales, are smooth obelisks, stoic amid the trembling grasses.

Back in the car, and moving ever onward,we glide towards our next stop, Shamakhi, as Azerbaijani pop music crackles and fades on theradio. The Caucasus Mountains to one side mark our progress while we make ear-popping climbs and falls. On the approach into town, once on eof the major trading centres of north-westernAzerbaijan, roadside clearings appear, occupied by men standing beside what looks, from a distance, to be coloured vinyl LPs hanging from clothes lines and wrapped in plastic. These bright discs, it turns out, are turshu lavash, made from sun-dried fruits, which have been submerged in water, seeds removed, then boiled to create deliciously sticky sweets, for which the going rate is a measly 1 manat (about 80p).

These viscous concoctions range in colour from honey-orange to beetroot-red. Each selecting a desired flavour, we gnaw at them while browsing the array of fresh watermelons and home-made honeys, also for sale. One elderly salesman offers a clutch of pale-blue, postbox-sized beehives, standing just yards behind him. It would be hard to get any closer to the source of the food, unless you were stung by it.

Little remains of the ancient town of Shamakhi today. It’s a bijou settlement, where cows amble down the main street and taxi drivers yawn outside tiny bazaars. The arresting double hill just beyond the modern centre still features the remains of the once impenetrable Gulistan Fortress. Erected by Shirvanshah Gubad in the 11th century, this was one of what was believed to bea network of more than 350 fortresses used to protect the Shirvan people from invaders. Persians (and later, in the 19th century, Russians) destroyed the mini state of Gulistan, which today is little more than a crumbling tower standing alone and unloved.

As a shepherd hustles his flock of sheep across the meadows up ahead, we idly discuss the verity of recent stories circulating the town, which claim that some amateur local diggers unearthed gold from underneath the tower before fleeing – never to be seen again. The evening draws closer, casting flamingo- pink flecks across the sky, and it’s time we made a move again. We drive upwards from Gulistan’s last remains and appear to also travel back through time to the village of Ivanovka. Still run, successfully, along the collective farm system of the Soviet Union, this town feels every inch like a tiny slice of bucolic, atavistic Russia.

Formed by a small community of dissenting Christian Russians, forcibly relocated from the motherland to the Caucuses by Tsar Nicholas I in the 19th century, Ivanovka is reputed to be home tothe richest farmers in Azerbaijan. There is certainly no sign of ostentatious wealth to be found on my visit. Instead, there are oak-tree-lined boulevards full of immaculate Russian-style timber houses with steep, sloping roofs leading up to a series of small hills. These hills look out upon a vast open vista of fields and mountains that makes me feel as if we could be on the set of our very own Spaghetti Western – if only the ambient noise of cow bells and shouting children were replaced with a Morricone soundtrack.

While Ivanovka operates as a commune, just 10km away, down a tiny winding lane, lies a conspicuous and utterly surprising manifestation of private enterprise and luxury. Château Monolit is a temple to Azerbaijani wine. Open since 2007, the château, denoted by its enormous, garish mural on a grain silo by the front gate, has spacious comfortable guest cottages, a pool lined by swing sofas and a gargantuan new limestone cellar housing more than a million bottles.

Propping myself up against the sturdy wooden bar in the tasting room, I sip the Monolit Médoc – a soaring orchestra of a red wine – and find it dazzling; not subtle exactly, but most certainly compatible with a rare slab of sirloin. The château is fitted out with state-of-the-art wine-making and bottling equipment from Italy and France, but the uniquely Azerbaijani element comes from the use of local grapes, matraza and saperavi, as well as the all but ubiquitous cabernet.

Chingiz and I loiter by the pool as the sun recedes. “There aren’t enough wine drinkers in Azerbaijan who appreciate this,” he observes. “You can buy wine from every corner of the earth in Baku these days but our own wines don’t get much of a look-in.” Somewhat reluctantly we haul ourselves up out of the gently swinging sofa to continue our journeyto Gabala, where we will stop overnight.

The sky has turned dark and grey and raindrops hurl themselves against the car’s windscreen as we negotiate lanes lined with plane trees and sopping fields. Every so often a clearing at the roadside comes into view where, invariably, a family, sitting on plastic chairs under a tin-roofed canopy smothered in fairy lights, is taking a meal-stop on their own journey. This road runs straight through Azerbaijan’s oldest city, Gabala, once the capital of ancient Caucasian Albania.

Slap bang in the middle of the old Silk Road, the town’s former important regional status was documented by Pliny the Younger, a magistrate of ancient Rome, who, when travelling through, noted that the town was thenknown as Kabalaka, ruled over by Sassanids, Khans, Persians and Mongols. There’s still a perceptibly mercantile thrust to the modern town, filled as it is with open-doored cafés, merchant stores and the shouts and yelps of market traders. The ancient town, however, 15km away, is a mournful and forgotten site bearing little of its previous grandeur, bar a few humps and a couple of low walls.

After a night at the plush new five-star Qafqaz Riverside Hotel on the edge of town, complete with grand piano in the lobby and beige- and grey-hued rooms so huge you need a trail of breadcrumbs to find yourway out, we’re back in the car and heading along arrow-straight country lanes. They are swaddled on either side by forest and tiny nooks, where smoky open grills, covered in racks of kebab meat for passing travellers, are tended to under verandas.

“This is my favourite place in all of Azerbaijan,” concedes Chingiz, as we motor slowly into a soporific-looking town, cut in two by a river and surrounded on three sides by tree-smothered mountains. We have arrived in the ancient silk-making centre of Sheki, a town that not only wows my guide but also impressed General Rayevski, a friend of the great Russian author and poet Alexander Pushkin, upon his visit in 1826. “Our camp is in a forest of pomegranates, tamarisks and plane trees,” he wrote to Pushkin. “Sheki is wonderful; it is Bakhchisarai, taken on a larger scale.”

It’s not known whether the estimable Rayevski stumbled upon the Khan’s palace in the centre of the town behind a suitably forbidding stone fortress, but it’s hard to imagine that he wouldn’t have been bowled over by what is quite simply one of the most beautiful buildings in the Caucasus. The Turkish poet, playwright and author Nazim Hikmet once wrote of the place: “If there were no other ancient structure in Azerbaijan, it would be sufficient to show the world nothing else but the palace of the Sheki Khan.”

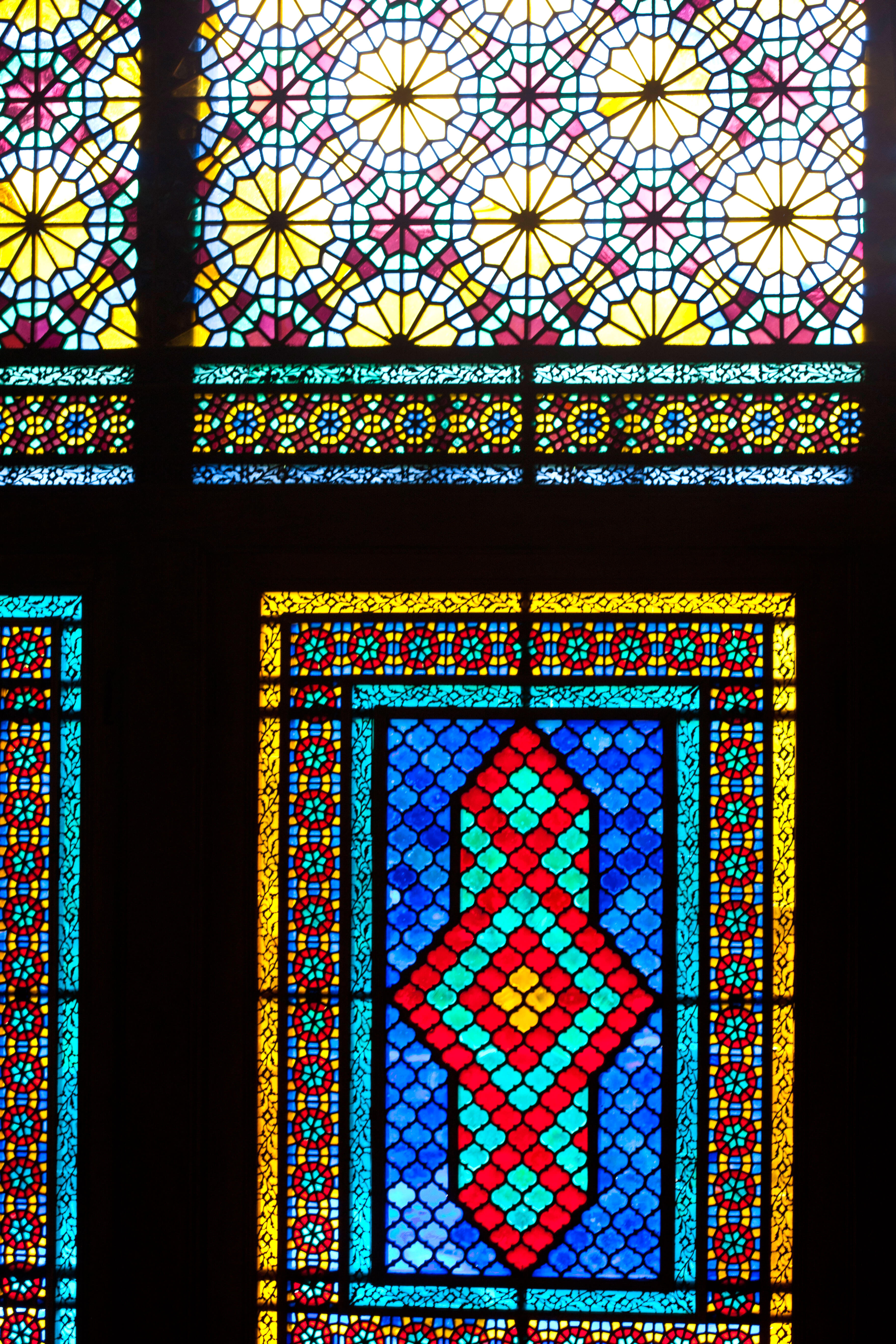

Thanks to recent renovations, the palace looks every bit as dazzling as it did upon completion by the master poet and architect Hussein Khan in 1762. It’s a squat, rectangular, two-floored building set in gardens filled with ponds and soaring chinar trees. Astonishingly, not a single nail was used in the palace’s construction – the wood and Venetian glass all slot together in a formula long since lost to history. Inside its six rooms are head-spinning mosaics of plants, vases and flowers, and murals depicting horseback battles. Every inch of space is covered in intricate patterns and the light from the multi-coloured glass bounces, refracts and sparkles upon the walls, creating an effervescent yet calming panorama.

It was perhaps not always thus. In the times of the Khan one of the upstairs balconies was used as an amnesty platform, where the ruler would dictate to the crowds below which criminals in the town would be sentenced, and which would be set free; decisions that were made on a completely personal whim.

Sheki’s reputation among Azerbaijanis isn’t entirely based on history, though. The town has acquired legendary status across the length and breadth of the country for its production of halva, the insanely moreish, sticky sweet that has been made in the town for at least two centuries.

Striding across town from the palace, we stumble upon a tiny shop, with a pink-tiled interior, called Ali Ahmad Dayi (meaning ‘Uncle Ahmad’). Slabs of delectable-looking halva on huge, round metal trays are being sliced and boxed up for a lengthy queue of lip-licking locals. Made from rice flour, honey, sugar, water and locally grown nuts, halva tastes more similar to nougat than its close relative paklava, and is eaten in vast quantities – washed down with black tea and lemon – at seemingly any time of day. Trying to deflect the attention of a couple of overenthused bees, we gorge ourselves from two boxes each. That night we stay in a converted 18th-century caravanserai, with its atmospheric arched inner courtyard and enormous domed entrance hall still intact, before leaving Sheki in the morning for the open road.

The car heads north as the landscape gradually morphs into pure Clint Eastwood country. Freight trains slide over tracks that slice down the middle of wide canary-yellow barley fields. In the background the crenulated peaks of the mountains glint like arrowheads in the midday sun.

The landscape looks as if it could feasibly continue in this vein for days, but there are still, even this far north, small points of urbanity. As afternoon approaches, we enter Zagatala. This small, tidy town, with abstract murals painted daringly on to the sides of cottages and immaculate squares filled with dozing dogs and pensioners, has a vital role to play in military and movie history. Today, it is out of bounds to visitors due to its continued function as a military facility, but Chingiz and I can’t resist a stroll around the baleful and seemingly unguarded stone walls of a Russian fortress. Its vast wooden gates seem to come straight from a Christopher Lee horror film. “Everyone in Azerbaijan has to do national service,” Chingiz tells me. “So I don’t find anything strange about places like this. Anyone is welcome to look around the outside of the fortress; people understand how important this place is.”

Built in 1830 as protection from invading mountain tribes, the fortress was where rebels from the Potemkin battleship – a famous revolutionary moment immortalised in Sergei M Eisenstein’s iconic 1925 film – were held. The film was banned by the Soviet Union due to the Kremlin’s belief that it could flame dissident unrest against the regime; now, nearly 30 years after Azerbaijan reclaimed its independence, the fortress remains a small yet potent reminder of a distant mutiny.

As we drive on to Balakan, the highway narrows to a thin two-lane strip of dusty asphalt lined with orchards and meadows. The cinematic landscape earlier has been replaced by a lush, verdant panorama of distant forests. Traffic disappears, to the point where herding shepherds and horse-riding farmers constitute the only human distraction to this sleepy scene. Balakan is the final stop before the Georgian border and belies the usual soullessness of border towns, with a restrained series of wide boulevards, barely frequented cafés, Soviet-era ‘people’s parks’ and an atmosphere of insouciant civility.

The next day, after a comfortable sleep at the new Qubek Hotel, we climb the minaret in the centre of town, where my story began. And later, back in the car, we drive through a suburban sprawl of pastel-coloured, single- storied houses, wide, surprisingly Californian-looking boulevards and lawns where dogs somersault through sprinklers. We have just one final stop to make before embarking on the long trip back to Baku.

Backtracking to Zagatala, we venture into the town’s nature reserve, despite it being officially closed to the public (a quick call from the hotel staff grants us access – and a local guide). Our 4×4 cruises along a vast, dry riverbed peppered with boulders and inhabited only by cows and a scattering of beehives, until we come to a roaring set of rapids, surrounded by drunkenly angled trees and a tiny, rusty-metal footbridge. “Nobody ever comes here,” says our local guide, also named Chingiz. “We want things to remain as they are, which is why the park is closed to the public.”

Undisturbedby modernity, we sit cross-legged in the grass and eat flatbread with kebab meat, tomatoes, cucumber and pints of fresh ayran (sour milk flavoured with mint). Birdsong and the crash of the river are the only sounds we hear.

“Azerbaijan doesn’t always give away its beauty easily,” Chingiz concludes as we begin inching our way back to the 21st century. “You have to want to travel and you have to enjoy the road to see the best of this country. There is an old saying that my grandfather used to believe in. ‘If your heart yearns for the road, then your head will do the rest’.”

And this highway, although seen by few Azerbaijanis and even fewer outsiders today, still has the capacity to move the head and the heart onwards towards further adventure.

A version of this story featured in the Autumn 2012 issue of Baku magazine.

Photography by Jonathan Glynn-Smith