The Japanese art of wabi-sabi celebrates perfection within imperfection. But what happens when you mix it with industrial concrete? Mark C O’Flaherty finds out

As Carrara marble is to Europe, so concrete is to Japan. It is inherently modern – man-made not mined, unprepossessing and austere. It is matter-of-fact and contemporary, yet also inherently 20th century, which makes it typically Japanese. Here is a country that feels like it exists 100 years in the future, but, at times, is stuck in the past. Concrete is like paper: you can copy and extend an idea to extravagant lengths. You can knock it down, rebuild, repeat … That’s the story of post-war Japan.

When self-taught architect Tadao Ando reproduced his Church of the Light for a retrospective of his work in Tokyo last year – Tadao Ando: Endeavors – he was copying his own landmark. It was a place out of place, and yet, it made perfect sense too. The 1989 original in Osaka incorporates one of the most famous interiors of the last 100 years. It is an austere, bunker-like place of worship, with a cross-section of negative space behind the alter – a Modernist cruciform that bleeds light into the otherwise sombre environment. It has become iconic, and a place of pilgrimage for people obsessed with design. But also, it’s a simple structure that could be reproduced economically anywhere.

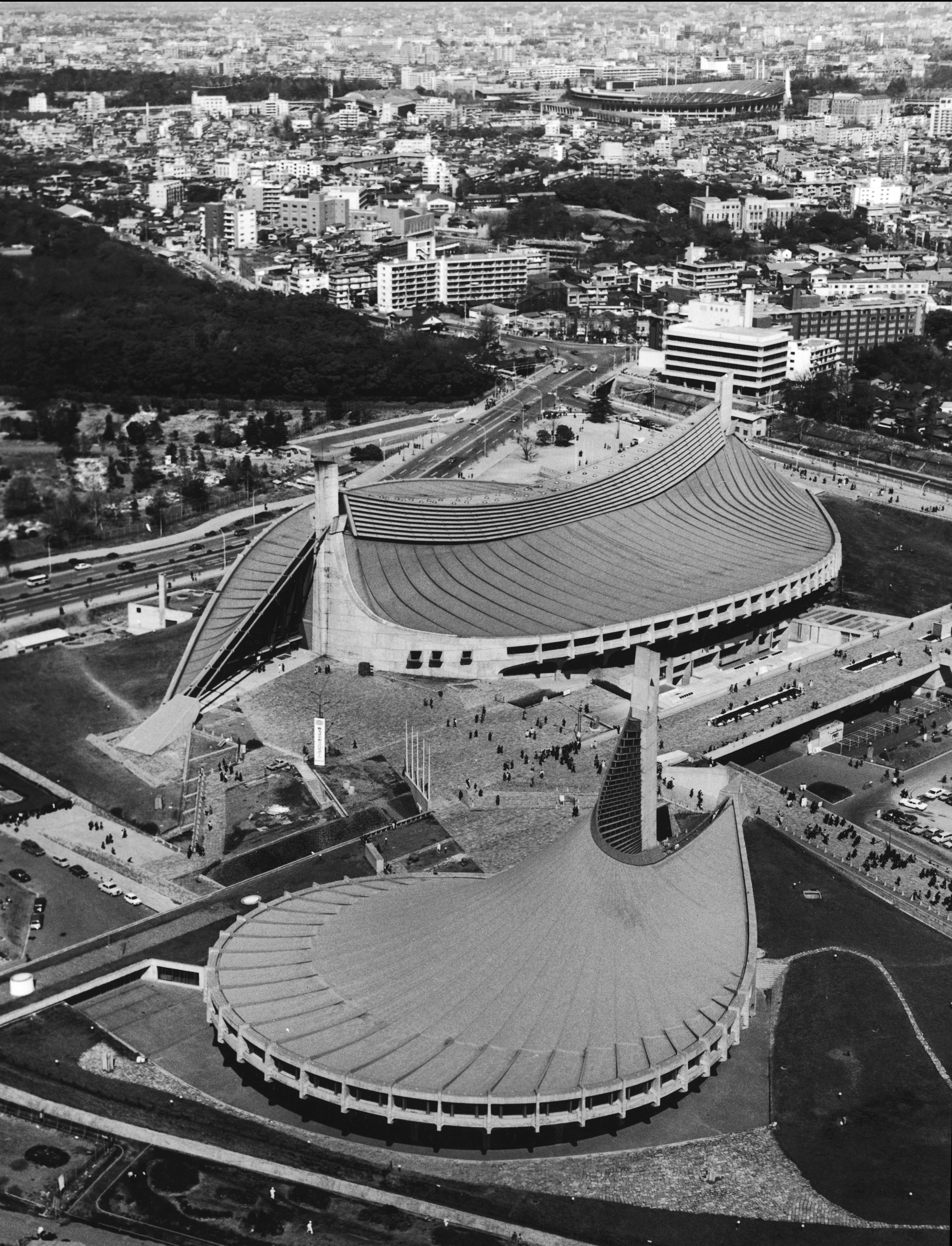

Some of Japan’s most famous landmarks are concrete, including Kenzo Tange’s Yoyogi National Gymnasium, built in 1964 for the Tokyo Olympic Games. It represents a revolutionary approach to architecture in the country – mixing traditional temple-like silhouettes with a curved concrete base, and a playful geometry that predates Gehry’s computer games by decades. In a city with undistinguished 21st century architecture, it’s a rare beauty. Everything about its concrete curves captures a time of optimism and ambition.

An aerial view of the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, circa 1965. Designed by Kenzo Tange to house the swimming and diving events in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, it is now a major venue for basketball and ice hockey.

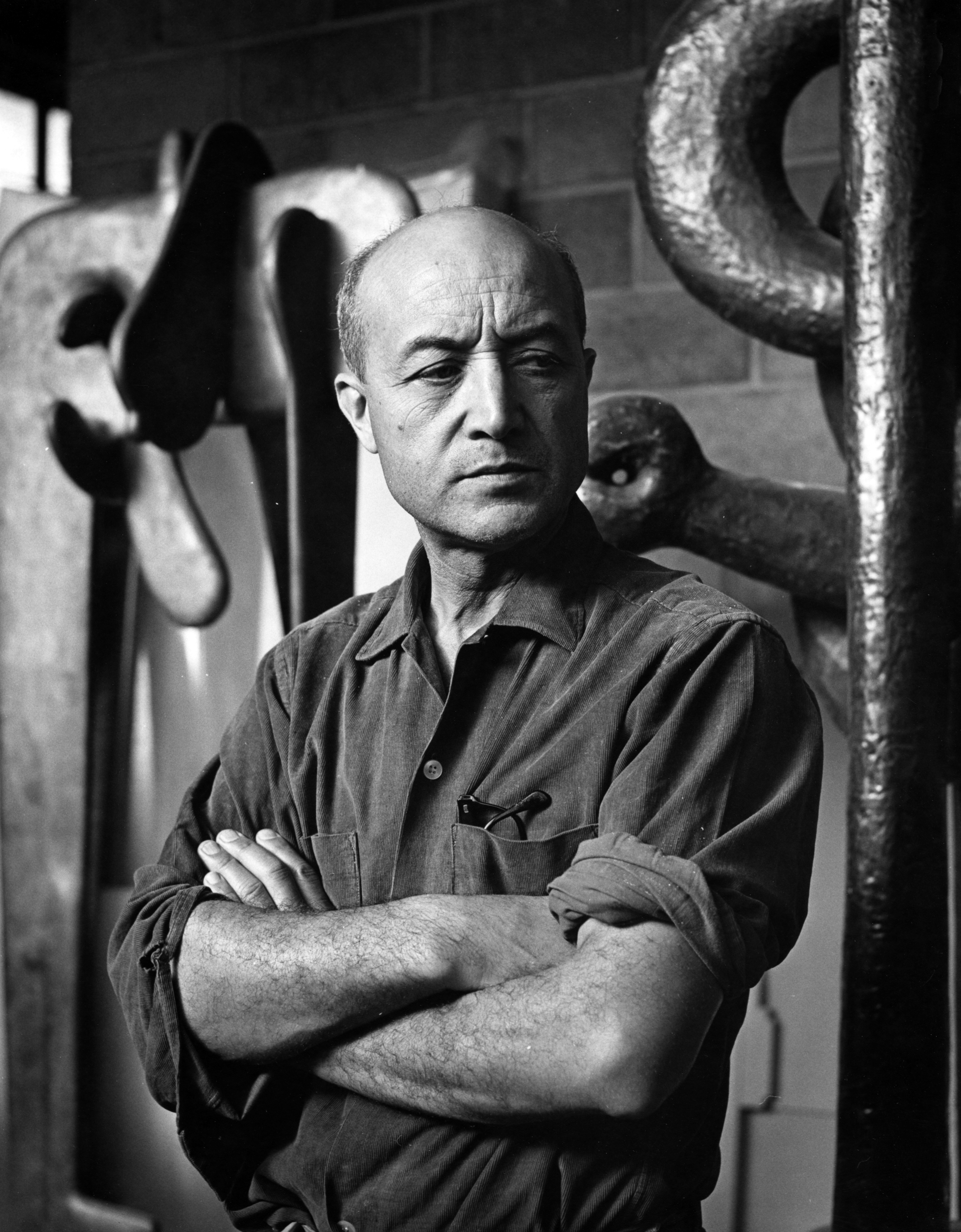

The sculptor and designer Isamu Noguchi’s final project – Moerunum Park – makes grand use of the material. Noguchi’s work includes the cast-concrete railings for the Peace Bridge in Hiroshima and he died in 1988, but his park in Sapporo, including a concrete cone with slides cut into it, wasn’t completed until 2005. It’s a space that’s all about play: expansive and inspiring, few spaces with such a purity of vision and absence of commerce exist. a place that exists purely for pleasure, it’s the most generous kind of design.

Tadao Ando – who called his dog ‘Corbusier’, in tribute to the master of Modernism – has had a long career in concrete since his Osaka church opened its doors. His 2007 21_21 Design Sight gallery for Issey Miyake in Tokyo is an art bunker sliced up with lines of light, while his work on the art island of Naoshima is an architectural wonderland, with fabulous geometric shapes fashioned out of his usual material. Throughout the day, the moving sun transforms the interior and exterior spaces with angular shadows. The designer is fastidious about fabrication: his concrete is created using plastic-coated plywood so that it is entirely smooth, but its surface is punctuated by the holes left by the plastic cones that keep his form-ties in place while the concrete sets. Here is industrial wabi-sabi – the marks left by the construction make for an incidental, unfinished quality.

The way concrete decays can make it particularly pleasing – like walking through the set for a science fiction movie. Ando’s work is pristine, but one wonders if any of it will end up like the buildings of Hashima Island (main image). Here, there are fresh, contemporary concrete walkways at the dock that act as viewing points for daytrippers from Nagasaki, alighting to see the fabulously derelict, long-abandoned mining city that incorporated the first reinforced concrete structures to be built in Japan. The island was first developed for industry in the late 19th century, but it wasn’t until the 1910s that reinforced concrete was used for new buildings there – perfect for the apocalyptic ocean weather that battered them day and night. Today, it is a city in bits, and a distant curiosity, but the scale of the rubble and graphic lines that still stand conjure up a ghost of something still incredible.

Images courtesy of Getty Images and Masaya Yoshimura