Harvard University’s George Church is a molecular geneticist, whose roster of achievements includes assisting the development of DNA sequencing, heading the race to edit the human genome, and pioneering the effort to bring back extinct creatures such as the woolly mammoth. We have a duty to put these technologies to work, he tells Michael Brooks

You’re more of a bio-hacking engineer than a traditional biologist. Where did that come from?

I grew up on the mudflats in Florida, and every day I would wander around them looking for new creatures. The other thing was that my adoptive father was a physician, and I was fascinated by the technology that he carried around on his house calls. I was also inspired by a visit to the New York World’s Fair in 1964. There was a huge amount of technology on display, and I was instantly addicted to the idea of progress and the future. Those three things coalesced over time.

In the past decade, our ability to read, write and edit genomes has accelerated enormously. Is this the best time to be working in genetics?

Everything does seem to be getting more and more exciting. Progress is exponential: we have helped bring the costs of reading DNA down 3 millionfold in six years, when it was predicted to take six decades. Gene editing is promising, yes, but the technology still has a way to go.

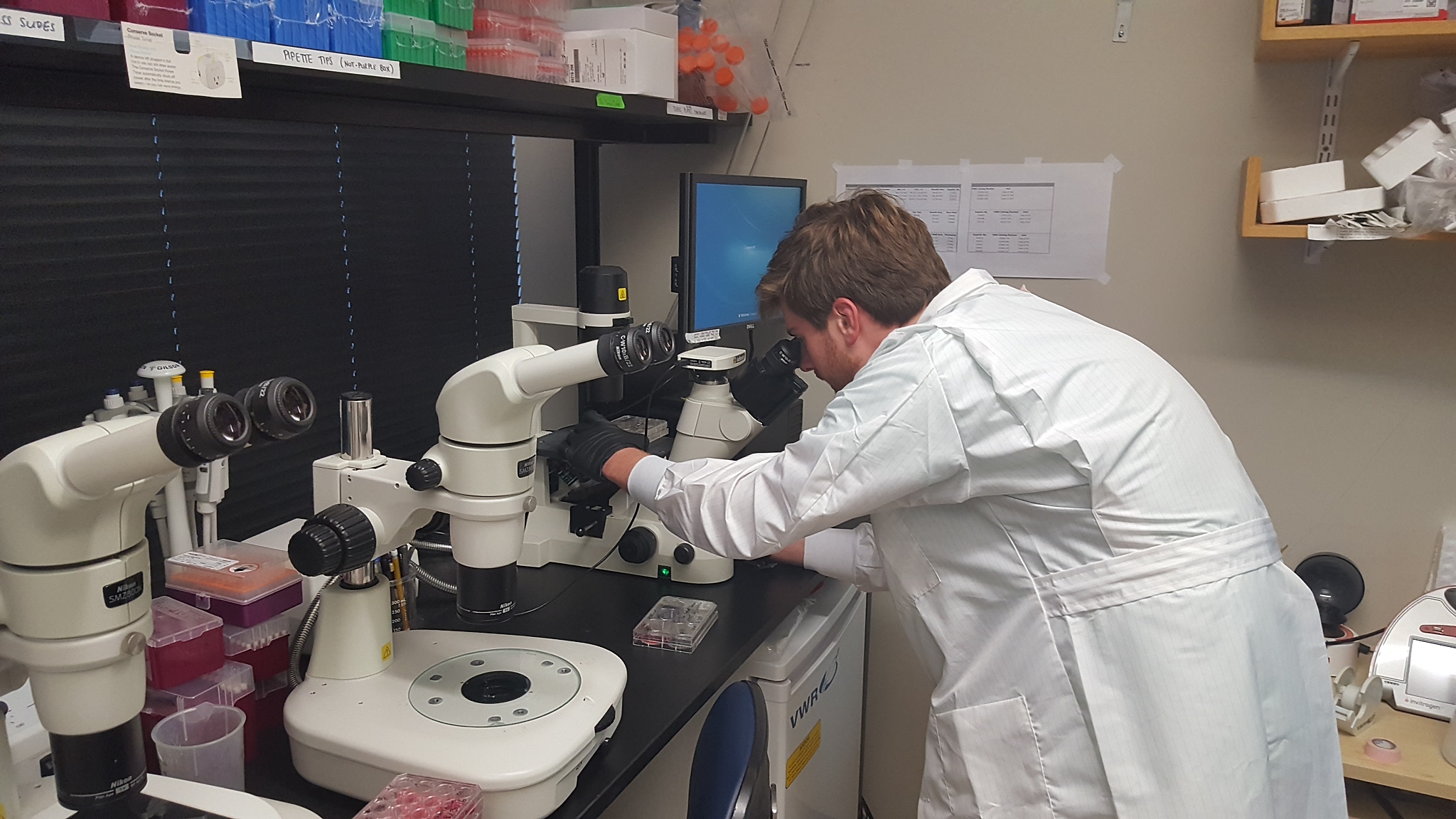

A scientist looks at engineered elephant cells, edited to introduce ancient woolly mammoth DNA, under a microscope

Are you making progress in your efforts to bring back the woolly mammoth?

We are submitting four papers on various aspects of it this year. That doesn’t mean we’re going to have a herd of woolly mammoths roaming around in the Arctic tundra; I have no idea how far away that is. But it turns out the genome editing part is pretty easy – we’re getting good at that. And reading the ancient DNA turned out to be easy, too; we have now analysed 24 elephants and mammoths and that’s allowed us to pick the right things to prioritize. It goes beyond de-extinction, in that you’re making something that really never existed before: an Asian elephant-mammoth hybrid. We are focused on conservation, not de-extinction, and are trying to reinvigorate an ecosystem, the Arctic tundra, using elephants made resistant to the cold.

Why does the tundra matter?

There are 1,600 gigatons of carbon under there [this is the amount of carbon dioxide that can be released into the atmosphere], and it’s at risk if the tundra is left to decline. Every square kilometre of Canada, Alaska and Russia that is not being used should be a research priority. We should be asking, what’s the best composition of plants and animals for reversing global warming and trapping carbon in Arctic grasslands?

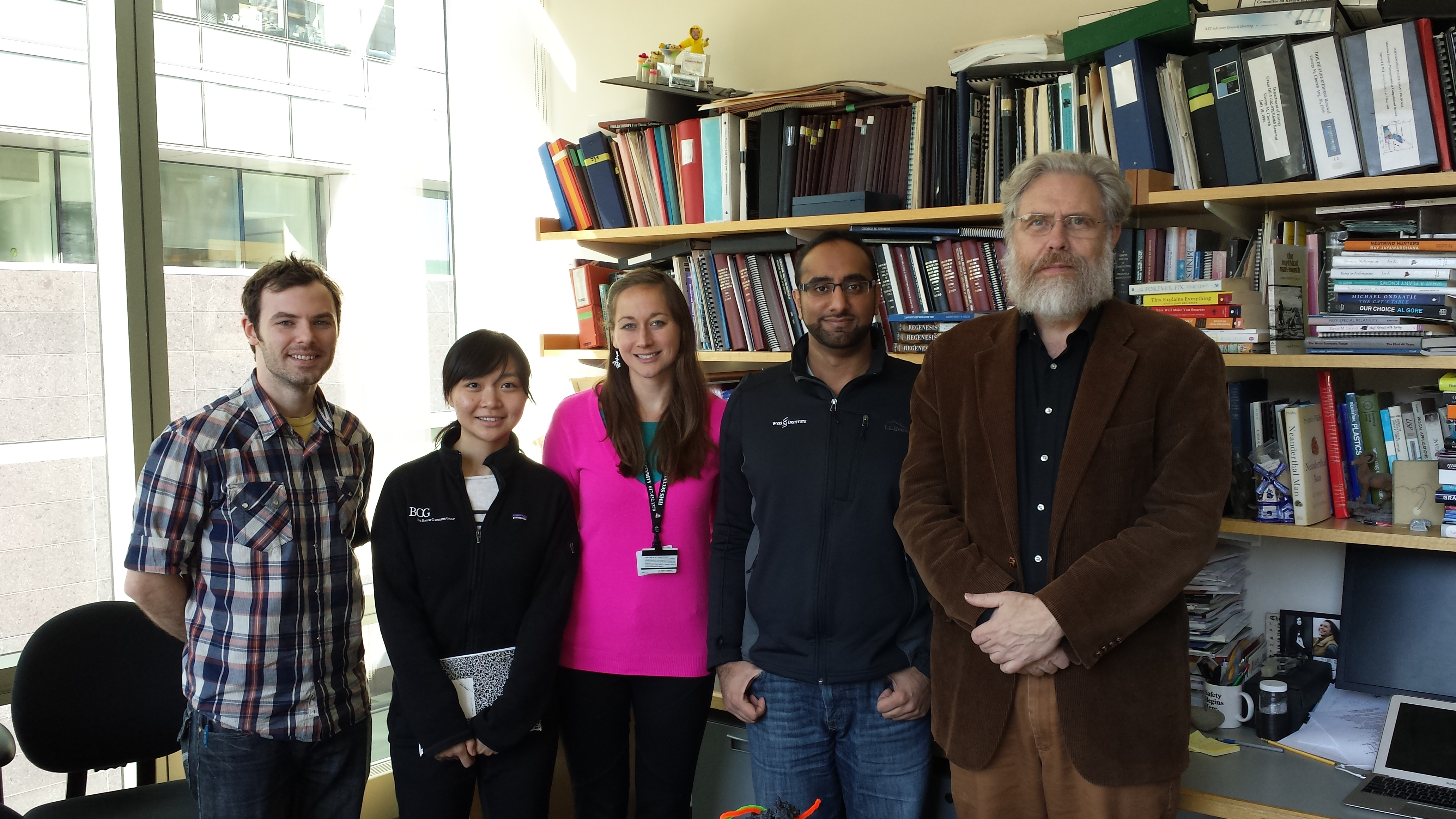

Dr George Church with members of the Harvard woolly mammoth de-extinction team that first launched the project

Can gene technologies change the world?

The current revolution in our ability to read and write DNA will affect everything: agriculture, medicine, industrial processes, ecosystem management, problems with invasive species. I can give you an example from our lab: we are working on a way to make any species resistant to all viruses. So, no more foot and mouth disease, for example, where you have to burn all your animals, wiping out four years of profit in a few months thanks to an epidemic that can go worldwide. We’ve already shown that we can make a species multi-virus resistant, and we’re now extending that to various agricultural plants and animals.

Is there enough caution about these technologies?

I’m one of the loudest voices about caution. I’m heavily invested in safety engineering, and I’ve written nearly 20 papers on bioethics. I’m an optimist, but it’s complicated – everything worries me. But because people worry so much about new technologies, I worry that we’re going to not do something that could save a lot of lives and improve quality of life.

Scientists have fun in George Church beards with a young woolly mammoth enthusiast on a tour of the lab

You’re known as a bit of an eccentric, eating nothing but nutrient broth for years as a student, for example. Is eccentricity a spin-off of creativity?

I don’t think it’s cause and effect, but if you’re involved in improving the world then you’re probably a bit different. One of the dangers we face in the future is that we might squash some of our diversity. We make a big deal about ancestral diversity, but we also need to pay attention to neural diversity and the benefits it brings.

Photography courtesy of Harvard Medical School, Department of Genetics