Anil Seth is Professor of Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience at the University of Sussex, where he leads a cross-disciplinary group of researchers at the Sackler Centre for Consciousness Science. Here, he tells Michael Brooks about the high expectations placed on his discipline, and why a scientific understanding of consciousness is within reach

What inspired you to do science?

Like many kids, I enjoyed taking things apart. There was an old dental instrument factory in the village where I grew up and they used to throw out old machinery in the yard behind my house. I remember finding it fascinating to try to figure out how these things worked. But it’s one thing to find science interesting and another to be inspired to become a scientist. For that, I have education to thank. At every stage, the opportunity to go a bit further opened up, and I never stopped taking an interest.

Some people have said we can never understand consciousness. What’s your view?

I am confident that science will help us understand many things about consciousness, although there could be a residue of mystery that we won’t get to. But this isn’t so unusual – after all, physics doesn’t explain why there is a universe. In fact, there aren’t many disciplines of science where people are asked to solve the entire problem as the marker of success. Sometimes, we seem to expect more from a science of consciousness than from other branches of science.

What direction would you like your field to move in?

Consciousness science could benefit from worrying less about how and why consciousness is part of the universe in the first place, and focus more on what the properties of consciousness actually are and how they relate to the brain. There are good questions here: what is visual perception like? How does it compare to an experience of agency [being in control of one’s actions and the external environment]? What’s the difference between losing consciousness and a change of perception? I also think we need more emphasis on developing good theories that can guide our experiments.

Do you feel your work brings moral and ethical implications?

Definitely. For example, how we treat others, how we define social norms and make laws depends to some extent on the notion that we all experience the world in the same way. But we are finding that’s not the case; hopefully, appreciating this will make us more tolerant. Also, although the ethics are complicated, our growing understanding about the natural causes of our behavior and the nature of free will has consequences for the assignment of responsibility and how we might administer justice. I would hope the endpoint of this discussion would be less emphasis on retributive justice and more on rehabilitation.

Does the idea of scientists creating conscious machines keep you awake at night?

Not really, no! I try to push back against the idea that, as we build smarter and smarter machines, there’ll come a point where these machines inevitably become aware and then maybe take over the world. This assumption comes from a tendency to associate consciousness solely with intelligence. People still tend to assume that the mind is a software program running on the wetware of the brain. The metaphor of a computer has some value, but by no means should it be taken on fully. There are many differences between brains and computers.

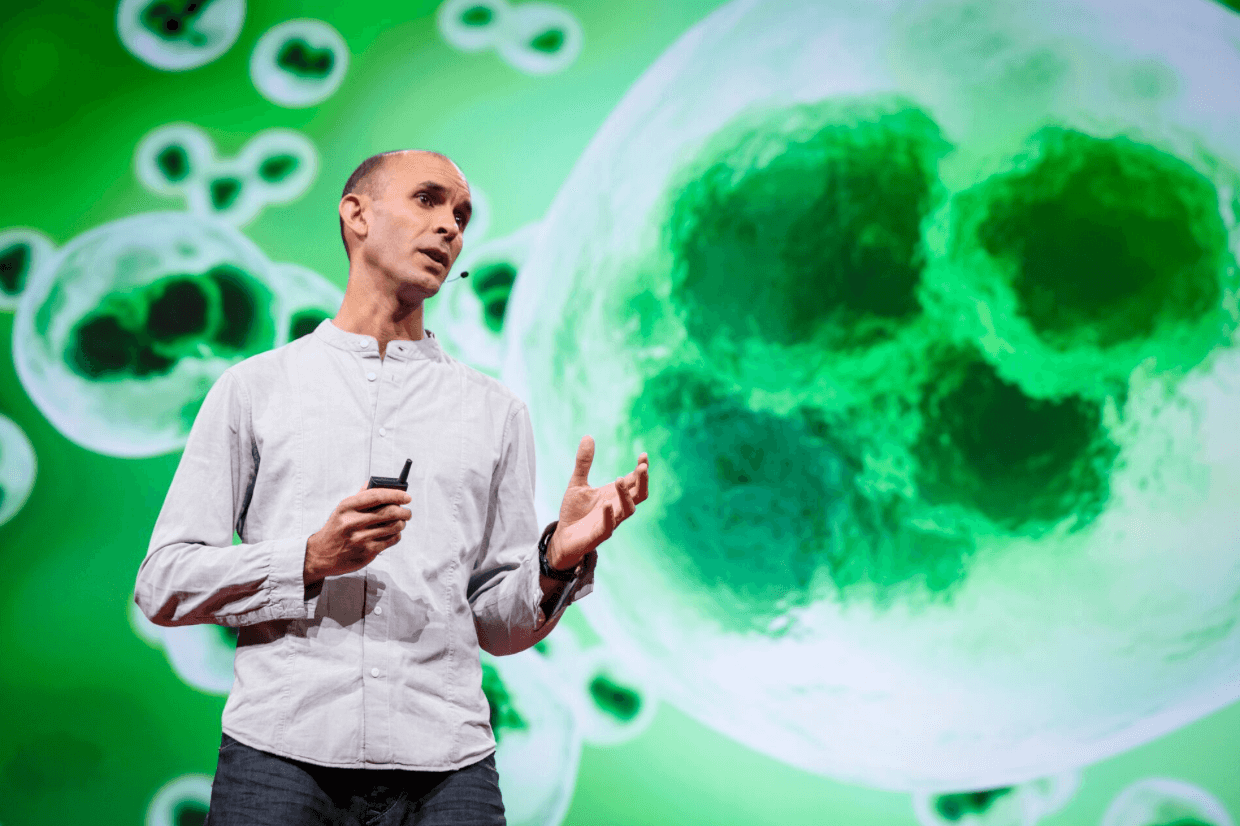

Your TED talk, in which you suggest that reality is something we hallucinate, has been viewed almost five million times in less than a year. Has that changed anything for you?

That was a great opportunity. There are very few platforms where a scientist can have such a broad reach, and I have been surprised and delighted at how many people have seen the talk. It has opened up other opportunities to speak and meet people, but it hasn’t changed much in the lab. We still struggle for funding in the same way!

What do you do to relax?

When I was working in San Diego, California, I used to go surfing three or four times a week. That’s a beautiful way to relax because of the enforced meditative state it puts you in; most of surfing is about waiting. But I don’t surf much now I’m back in the UK. I still play football – very badly. And when I can, I like to go paragliding. That’s the closest I get to the surfing state of mind.

Photography courtesy of Anil Seth