With the advent of the Kindle, it seemed there was no turning back from e-book world domination. A decade on, however, and traditional book stores are seeing a surge in popularity and hard copy books appear to be witnessing something of a comeback. James Parry explains why the experience of a printed book remains so appealing

It looked as though the publishing world might never be the same again. The launch in 2007 in New York of Amazon’s Kindle – widely regarded as the world’s first portable electronic reader – was hailed at the time as nothing short of a revolution that would determine the future of literature. The entire stock of the new gadget sold out in five and a half hours, despite a hefty upfront price of US$399, and it was then promptly unavailable for five months (which only made it even more desirable). Apple’s answer to Kindle, the iPad, was launched three years later and the seemingly inexorable rise of “e-books” surged ever upwards. In 2011 Kindle downloads outsold hard copy books on the Amazon website, several years ahead of the company’s own ambitious projections. “This is the future of book reading,” proclaimed author and financial journalist Michael Lewis, “it will be everywhere.”

A Kindle Paperwhite reading device is seen at a press conference in Santa Monica, California. (Image courtesy of Getty Images)

With conventional book sales falling and bookshops pulling down their shutters for the last time on what felt like every street corner, traditional publishers were struggling. Gloomy soothsayers predicted the end of books as the world knew them. But fast-forward six years and, oh my word (pun intended), how things have changed. The bookworms are on the march once more. In 2017 sales of physical books rose by four per cent, while e-book sales dropped by at least that amount (the third consecutive year they have fallen). An even greater disparity is predicted for this year. Remarkably, we’re now in the age of the paper book pushback.

How and why has this happened, and so fast? Partly it’s a price thing. Changes in 2015 in the contractual agreements between Amazon and the bigger publishing houses have seen the latter push up e-book prices to the point where now, for some titles, the electronic version is more expensive than the traditional format. But there are other factors pulling people back to print, and these have more to do with lifestyle considerations than simply the pennies in our pocket.

There had always been dissenting voices, of course. In 2008, at the height of the Kindle frenzy, Ray Bradbury, author of the sci-fi classic Fahrenheit 451, had announced that, “There is no future for e-books because they are not books.” And if that were not dismissive enough, he hurled one more insult: “E-books smell like burned fuel.” The point being, that real books have a delicious sensory quality to them, whether it be the crisp and pristine feel of one straight off the press and with no previous owner, or the dog-eared characterfulness of an aged secondhand paperback bought for next to nothing.

It’s a dimension not lost on Neil Hewison, recently retired after 30 years working in senior editorial positions with the American University in Cairo Press (AUCP), the largest English-language publisher in the Middle East. AUCP publishes most of its titles in print and e-editions simultaneously, but has found that the latter have struggled to achieve 20 per cent of market share at best. “Sales of e-books plateaued quite quickly after the initial excitement,” says Hewison, “with feedback from customers confirming what most of us already knew: that it’s hard to beat the look and feel of a beautifully designed and produced book.”

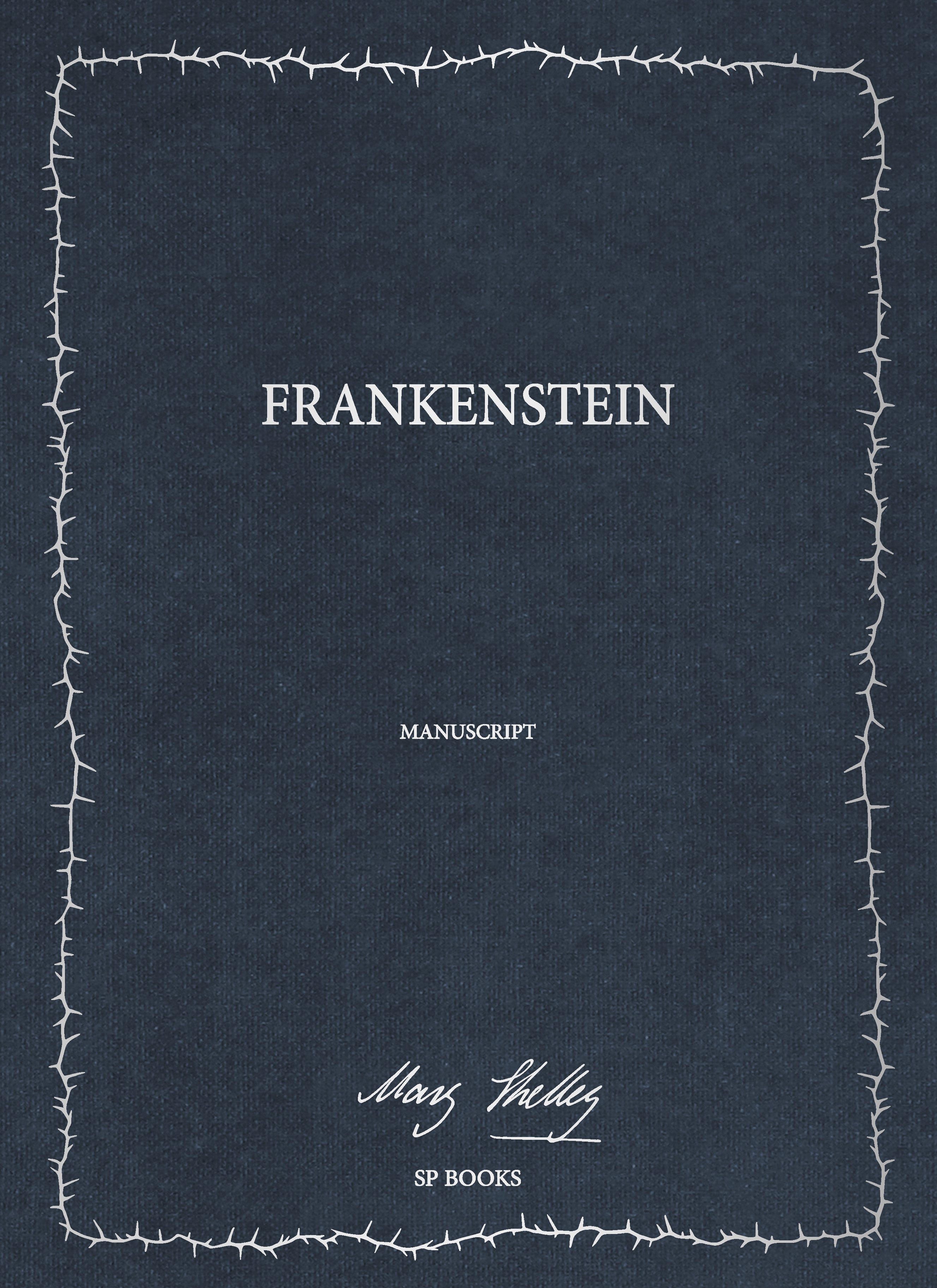

The cover of the newly-released Frankenstein manuscript by Mary Shelley (Image courtesy of SP Books)

Publishers have quickly understood how people still value the visual impact of high-spec and attractive books, not least as decorative items in their homes – the power of the coffee-table book endures. There’s some psychology going on, too. How many of us have sneakily enjoyed learning about newly made friends by checking out what books they have on their shelves when we’re invited to their home? It’s hard to do that when what they’re reading is secreted away on a password-protected tablet. And no one’s ever started up a conversation with a stranger on a train over a Kindle.

Meanwhile, many traditional booksellers who survived the e-publishing onslaught and other market pressures have repositioned themselves as cool places to hang out. Claire Dunne, owner of a small independent bookshop in an English market town – precisely the type of outlet that was going to the wall a few years ago – has prospered by diversifying. She sells both new and secondhand books, as well as stationery, and runs a popular café within the shop. “We’ve created an attractive destination in its own right, a place where people come to enjoy themselves and which happens to sell books,” she says. “Thousands of lovely books to browse, backed up by personal service. It really strikes a chord.”

Snuggling into a cosy corner with a cappuccino in a friendly bookstore has a more personal equivalent at home: the comfy sofa moment. There’s no electronic equivalent to the joy of “burying yourself in a book” in that favourite chair. It’s just too tempting while reading on a tablet or smartphone to switch screens and dip in and out, checking emails, status updates and messages. Hard to concentrate? This seems to be especially the case with millennials, the most likely demographic to suffer from screen fatigue. Surveys suggest that they are also increasingly prone to taking total (if temporary) breaks from online life, perhaps due to an oversaturation of social media. Real books might represent a welcome refuge.

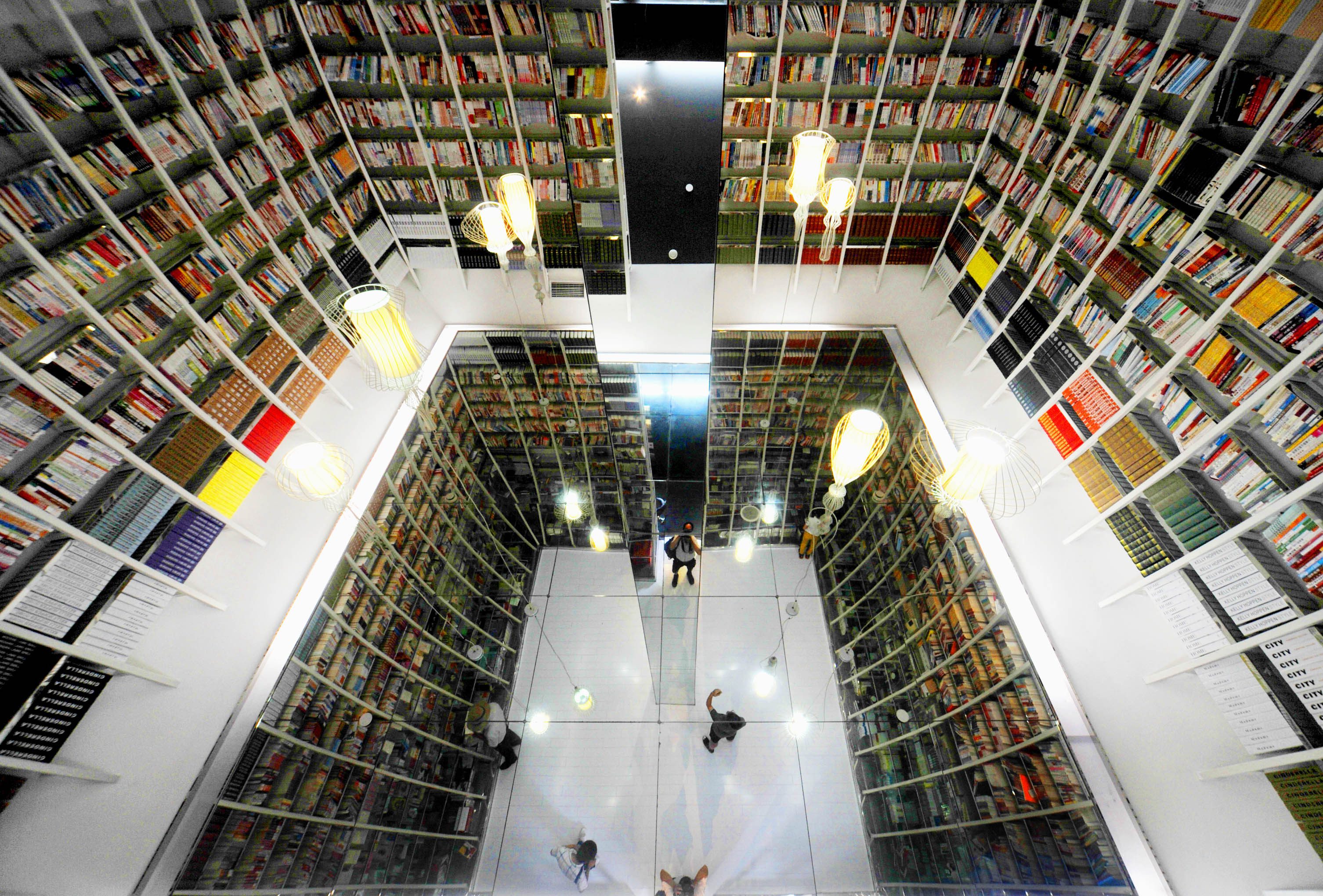

Nothing beats a good bookstore: Here we have an aerial view of a book retailer named Zhongshuge at Thames Town in th Songjiang District in Shanghai, China. Books are displayed under the glass floor in Zhongshuge bookstore, which was reconstructed by designers at Songjiang District in Shanghai. (Image courtesy of Getty Images)

There’s a more serious point to do with retention. Recent research by James Madison University in Virginia, USA, into e-textbooks suggests that people skim more, process more shallowly, and may retain less information when reading electronically rather than learning from traditional books. Even so, e-publishing has proved to be a boon for libraries and educational institutions. Electronic storage allows them to hold infinitely more publications than they would otherwise have adequate shelf space to accommodate. “The advent of e-publications has had definite advantages for researchers and academics,” says Margaret Willes, who was publisher at the National Trust, one of Britain’s leading conservation organisations, and is now a writer on social history. “Online journals are a hugely valuable resource, and many rare and otherwise expensive titles are now also readily available online, either free or for purchase. This has certainly increased access, but it can only go so far. Quality remains a real issue, particularly when it comes to reproducing illustrations. For me, e-books are very much an ‘as well as’, rather than an ‘instead of’.”

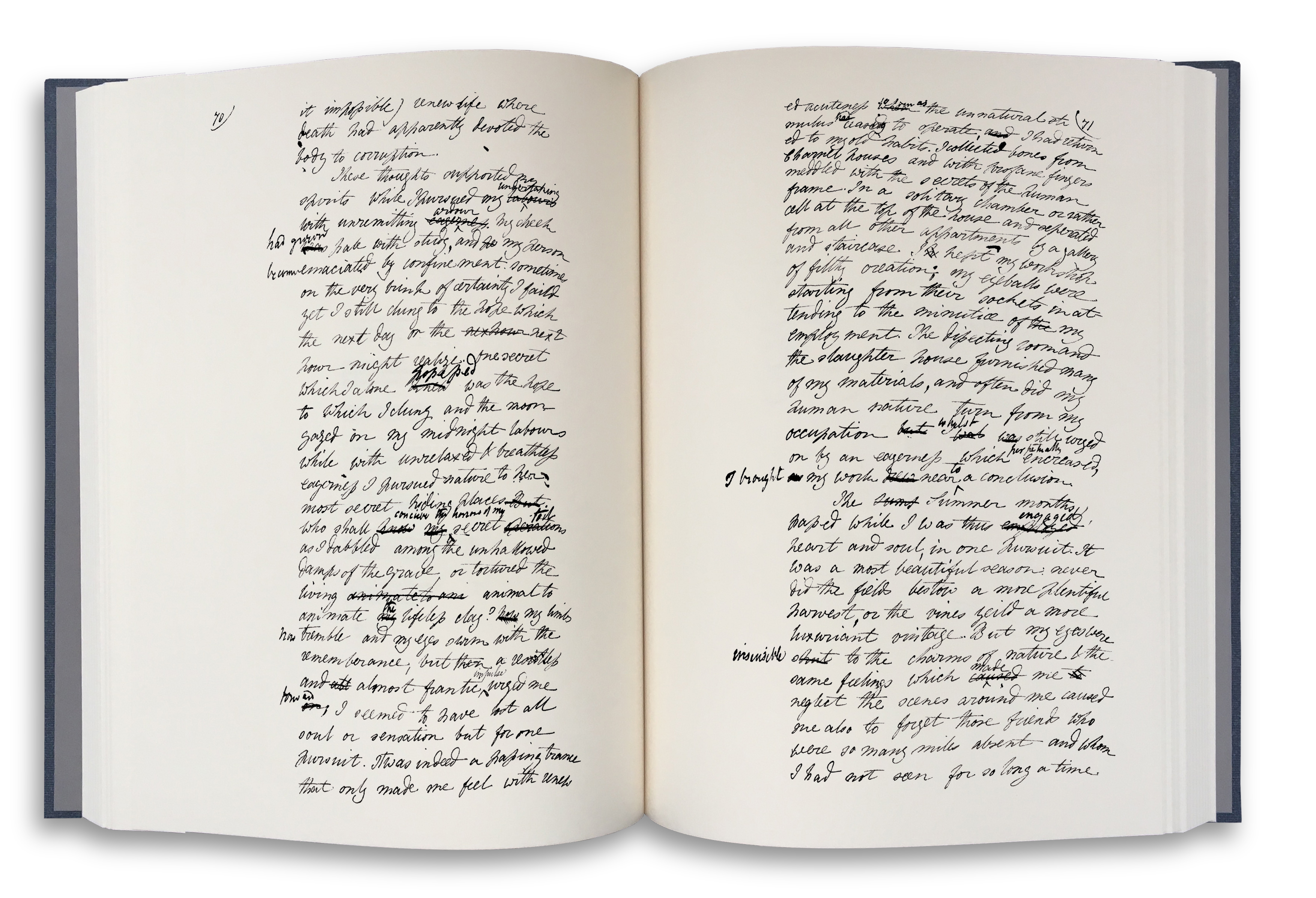

There’s the rub. E-books are primarily a technical solution, ideal for certain situations (when on the road being an obvious one), but aesthetically they kind of fall short. While we may be practical beings, we also like colour, style and beauty in our lives. How else can one explain the renaissance in real books, and the recent spike in interest in facsimile editions of original literary manuscripts? “The impact of new technologies in our lives in the past two decades has awakened interest in these beautiful historical and cultural testimonies,” says Jessica Nelson, co-founder of SP Books, which specializes in bespoke editions of great works of literature and is in the process of publishing a commemorative facsimile edition of Mary Shelley’s manuscript for her 1818 masterpiece, Frankenstein. “There’s a tendency to cherish handcrafted objects, so perhaps this is a case of authenticity winning over virtuality? The original handwritten word has such power because it creates an incredible intimacy between the writer and the reader.” Perhaps Friedrich Nietzsche nailed it in 1888 then, when he said, “All I need is a sheet of paper and something to write with, and then I can turn the world upside down.”

Images courtesy of SP Books and Getty Images