The tradition of carpet making is enjoying a renaissance, with Baku-based contemporary artist Faig Ahmed leading the crowd, particularly with his latest project, which takes him deep into the Amazon, discovers Tess Thackara

To some, carpets are mundane, utilitarian objects — background decoration to brighten a room or muffle noise. For others, they are nothing less than portals to the human subconscious. Count Azerbaijani artist Faig Ahmed in the latter camp. The Baku-based artist is known for his hallucinogenic carpet-cum-sculptures that combine research into ancient weaving techniques and iconographic systems with more contemporary imagery — the patchworks of colour that make up digital pixels seen at close range, or the effect of a computer glitch, where abstract forms seem to melt like liquid paint or wax. Looking at them can sometimes make you feel like you’ve accidentally fallen into another dimension. In one 2016 piece, a red and blue carpet filled with an abstracted pattern of flowers and plants appears to be possessed; a warped, mandala-like form emerges from the center of the textile and spills out of its edges.

Ahmed’s latest investigations into the world views and histories contained within rugs have recently taken him deep into the Amazon rainforest, along the Pisqui and Ucayali rivers where the indigenous Shipibo-Conibo people live. While the patterns woven into carpets around the world share certain similarities, the Shipibo’s, Ahmed explains, “are radically different from neighbouring regions and from all the rest of the world.” Made by Shamans and applied to the body, ceramics, and textiles, their kene or quene designs feature networks and bands of lines that snake — like the anaconda or cosmic serpent, or like “the paths of life… the meanders of the rivers,” according to scholars Nancy Feldman and Claire Odland, who produced a study on Shipibo textile practices — from one side of the object to the other.

The designs come from shamanic visions produced by consuming the hallucinogenic herb ayahuasca. The shaman, they believe, has a special relationship with the cosmic world, or collective unconscious, and transmits these patterns — a kind of code or language — to women, who then work the patterns into their craft objects. For the Shipibo, humans are the point of connection between the material world and “the invisible forces of nature,” as Ríos Cairuna, a Shipibo born in Paoyan, says in Feldman and Odland’s report. This may sound like a lot of mumbo-jumbo, but having spent time with the Shipibo, Ahmed is convinced of their deep bond between humanity and nature, the “relationship between biology and art” that “can be seen in the form of patterns,” he says. “We are the ones who came to this world recently, and must actively learn from the nature.”

How, exactly, does one go about expressing all of this in a carpet? In Liberation I (2018) (below), inspired by his journey to the Peruvian Amazon, Ahmed has gone for a rich, maximalist texture. A thick red carpet with a geometric border and a central flower-like motif, the piece erupts half way down into a voluminous wave of shaggy red fiber, as though it has grown a skirt. It seems to evoke the indigenous women of the Peruvian Andes who craft intricate textiles, with their wide, patterned skirts — as well as the profound relationship these patterns have to their makers’ worldviews. Ahmed’s carpet is a kind of life force of its own, capable of sprouting three-dimensional form. After all, the carpet is, Ahmed has said, one of the few objects that is entirely “complete.”

Faig Ahmed is not the only Azerbaijani artist with a particular fondness for carpets. Farid Rasulov famously covered an entire room in handmade red textiles for his contribution to the Azerbaijani Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale. It suggested an invitation to grapple endlessly with their coded messages, albeit a tongue-in-cheek one, since Rasulov insists on a lack of any hidden meaning in his work. And Eldar Mikailzadeh is something of a local treasure in Azerbaijan’s capital Baku, known as a master carpet artist who weaves colorful, otherworldly designs into textiles.

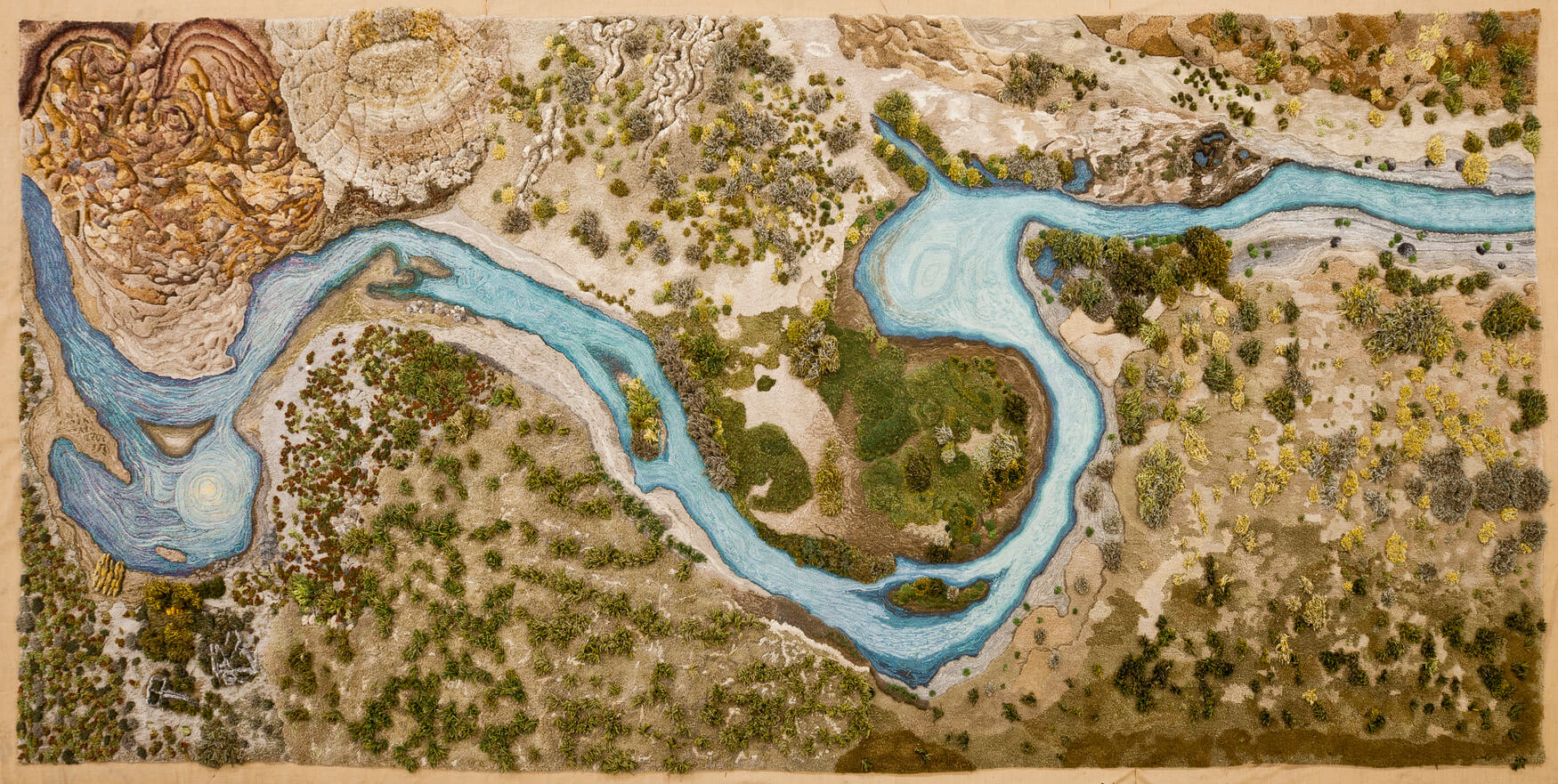

Contemporary artists in other parts of the world also employ this age-old medium — in many cases to weave political, feminist, or environmental messages. Iranian artist Farhad Moshiri’s Flying Carpet, for instance, is a fighter jet composed of a stack of 32 cutout Persian carpets — suggesting the relationship (or the dissonance) between culture and power. Argentine artist Alexandra Kehayoglou creates sometimes-vast carpet installations that mimic and honor the mossy, grassy textures of the natural world. They are an expression of her passion for the creeks, streams, and hills that she feels close to, and an effort to advance the preservation of the natural world. Meanwhile, Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum has in the past created textiles that are significantly less warm and fuzzy. Her Pin Carpet is made from thousands of pins, giving it a seductive, shimmering quality that belies its sharp, hostile nature.

Images courtesy of the artists, Francisco Nocito and Getty Images

Like this? Then you’ll love: The art of Saks Afridi | How the bitcoin revolution is changing the way we sell art