Only half of people across 10 of the world’s most biodiverse countries are very convinced that biodiversity – our ‘safety net’ or ‘web of life’ – is in decline, according to a recent Worldwide Fund for Nature study. With just 39% realising that we depend on nature and biodiversity for food, water and clean air, we spoke with Mark Wright, WWF’s Director of Science, about the environmental crisis, what we can all do meet to make a difference and what it’s like to work with David Attenborough

For the past four years, Mark Wright, Director of Science at The Worldwide Fund for Nature, has been working on Our Planet, which launched recently on Netflix. The series focuses on eight biomes, looking into the most pressing challenges facing our natural world. Here, he talks to Baku about the experience and why the year 2020 is so important for the future of our planet.

How did your career in conservation begin?

I have been interested in nature since I was a child. When I was little, my dad would check my pockets before I got in the car to see what I’d picked up. He started that habit after he once found I’d stuffed a dead squid in my pocket. My mum only discovered the dead mole in my jacket when flies started hatching in the wardrobe!

I believe every species on the planet has a story to tell, and some of those don’t give up that story too readily. Nature certainly favors the patient – but the rewards are huge. We have the most extraordinary life on this planet, and I’ve been hugely lucky in the things I’ve been able to see. But the things I have not seen are just as important. Even though I’ve never seen a polar bear or a blue whale in the wild, knowing they exist is meaningful, and knowing that others, including the next generation, may have the chance to see them makes me feel very content.

For the past four years you have been working on the Netflix series Our Planet. What were some of the highlights?

With such a passionate mix of filmmakers, photographers, production crews and scientists working together, there was often creative tension. We were all desperate to put our message out engagingly and factually.

I am delighted and proud with what we achieved here and believe we have managed to create something that is visually beautiful, as well something that has a really compelling and persuasive storyline.

How do the eight biomes work together? Which is the most important of the biomes?

Imagine a human operating with only one lung. While they can survive, it makes things a lot more difficult. Now, think about the biomes and our planet. It is possible that as we damage them, life will go on but, since the whole of life on earth is intimately interconnected, things will function far less smoothly. And certainly, things we take for granted will become less predictable; we are already seeing this to some extent with the changing climate. It is impossible to single out one habitat that is more important than another. They all play a critical role – sometimes unseen – but we absolutely need them all.

Why is the awareness that biodiversity is in decline so low?

As humans, we are removed from many natural processes. When we buy things in the shops, whether that is food or a laptop, we rarely think about the ‘natural production line,’ that helped create them. If we only see the final product, we don’t understand the processes and benefits that nature and biodiversity give to us. The fact that we don’t have that direct, hands-on engagement makes it easy to forget about what happens along the supply chain. We tend not to think about how much land or water was required to make a given product, or how far it has traveled.

I would love it if all school-aged children had to try and track the story of where seemingly mundane things, such as a fruit salad or a settee, came from so they start to think about how making them might have environmental consequences. I also think it should be compulsory to visit a landfill to bring home the impact of all those things we throw away.

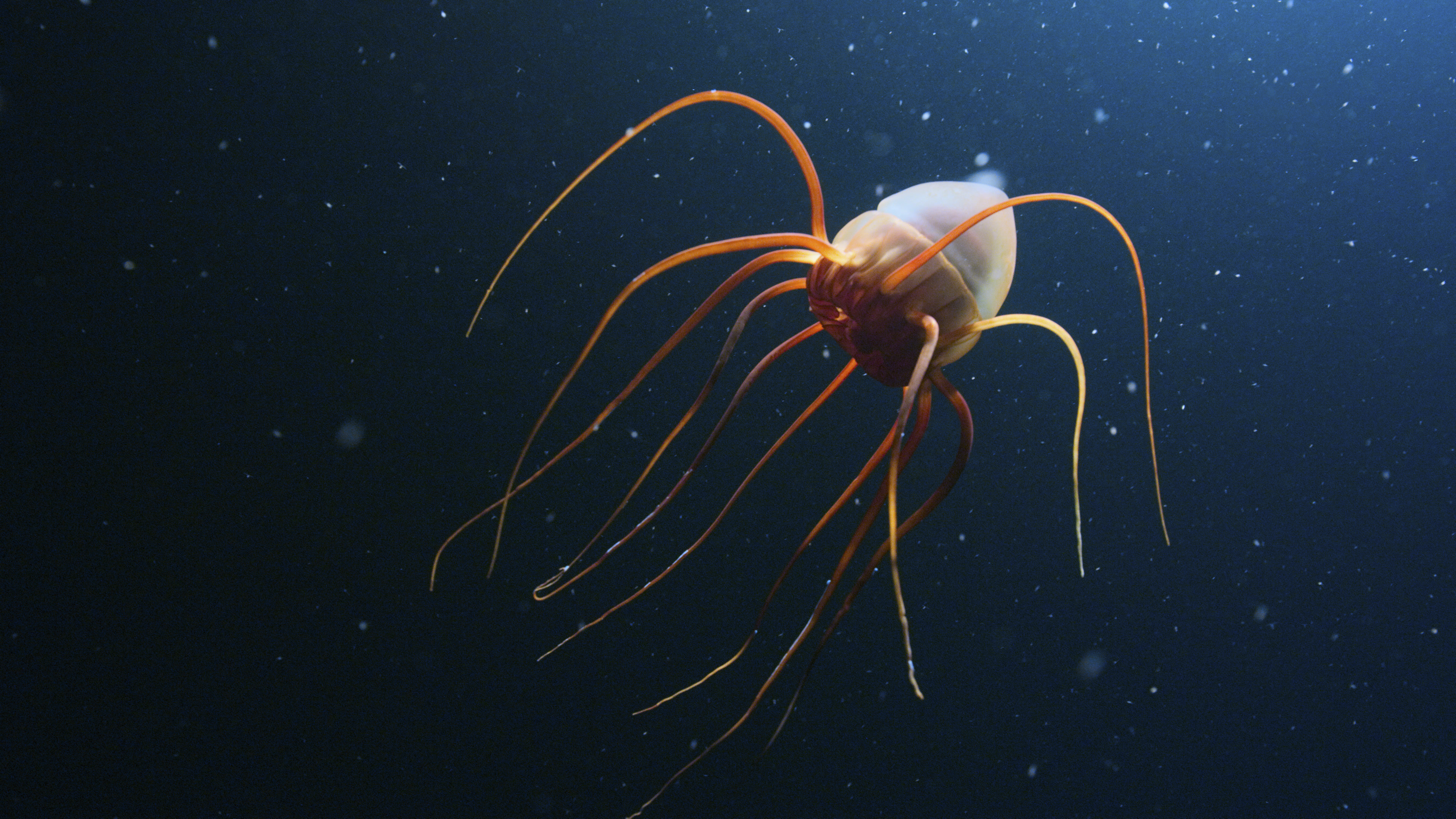

The jellyfish is Periphyllia or Crown Jellyfish, and is a deep water jellyfish. They live in every ocean to depths of seven kilometers and might be the most abundant of all jellyfish.

What does a world with shrinking biodiversity look like in 50 years? In 100 years?

We are at a unique moment. We’re the first generation to know what we’re doing to our planet, and the last generation who has the chance to put things right. Our world is under threat like never before. The latest in WWF’s flagship research series, The Living Planet Report 2018, shows that global populations of vertebrate species have, on average, declined in size by 60% since 1970 – less than a lifetime. We are using the planet’s resources faster than nature can restore itself.

If we continue on this path over the next 50 years, there won’t be an outlook for the next 100. Temperatures will soar, more and more species will become extinct, resources will become limited and the world will be a far less pleasant place to live in.

What are the 3 habits we can adopt now that will make a difference? And what bigger commitments can we make to help reverse or halt the damage?

Here are a few changes you can make right away:

- Minimise use of plastic. Use a bag for life, a re-usable water bottle and refuse plastic cutlery with your next takeaway meal.

- Try to use the car less. Why not just walk?

- Think about energy use at home. Switch to a green supplier and turn your washing down to 30 degrees, which uses around 40% less energy, and is just as effective.

- You can also make a change in your diet; moderate any meat and dairy consumption and eat more fruit and veg instead.

For more significant commitments, businesses have to ensure the products they sell us are truly sustainable, and politicians must be bold to secure a new deal for nature and people.

We have all grown up with David Attenborough and he is a huge inspiration to us all. What was it like working with him?

The team at WWF were delighted that Sir David Attenborough, a Worldwide Fund for Nature ambassador, agreed to narrate the English language version of the Our Planet series. He had a huge influence on me as I was growing up and we were hugely grateful for his support with this project.

Are there any other initiatives that you would like to share with us?

In 2020, we have the chance to put the world on a path to a better future, due to a historic coming together of key international decisions on environment, climate and sustainable development. It is a moment with the potential to put the health of our planet at the heart of our economic, political and financial systems. The Worldwide Fund for Nature is calling for concrete action plans with binding targets made by countries at a series of global meetings scheduled next year.

Leaders will essentially be mapping out a blueprint for a sustainable, and recovering, natural world. We can not afford to miss this opportunity; we have already lost far too much. This will shape the agenda for decades to come and will ensure that for the first time, the world has an integrated response to the three most important, interlinked issues of our time: climate change, nature loss and development.

But delivering this change will require more than commitments from global leaders. It will also require urgent actions from all of us, including businesses, young people, local communities, and civil society that together will reverse the trend of nature loss. This movement, along with governments, will be at the center of reversing the loss of nature. 2020 will be the moment when it comes together.

Images courtesy of Netflix, Ben Macdonald, Sophie Lanfear, Doug Anderson, Gavin Thurston and Silverback

Our Planet is available on Netflix now

Like this? Then you’ll love: The Climate Heroines changing the world | The Malay Archipelago: A Dramatic Tale of Natural History