Protecting rhinos from poachers has become a global conservation priority, but is it working? James Parry takes a walk on the wild side with the big beasts of Zimbabwe

It seems an odd thing to say, but it’s sometimes hard to see a rhino. How can this be, you ask, when they are so huge? And big they most definitely are, standing up to 1.8 metres at the shoulder, extending to four metres from tip of horn to tip of tail and weighing in at as much as 3,500 kilos. In the case of the white rhino, these impressive statistics make it the second largest land mammal after the African elephant. Colossal, but somehow elusive…

I am in Zimbabwe, in the Matobo National Park, several hours’ drive south-west of the country’s capital, Harare. This is rugged and dramatic terrain, with endless vistas of rolling hills strewn with massive granite boulders and bisected by thicket-filled watercourses and seemingly impenetrable tracts of woodland. It feels like real Africa, and surprisingly untamed given its history as a focal point for Zimbabwe’s pre-independence colonial life as Rhodesia. Cecil Rhodes, the British founder of that country, is buried here on Malindidzimu, one of the highest outcrops.

Driving through such awe-inspiring landscapes in an open jeep, I can understand why anyone might like to end their days here. The park was established in 1926, one of the earliest of its kind in Africa and based in part on a bequest from Rhodes himself. Now a World Heritage Site, it covers over 400 square kilometres of the much more extensive Matobo Hills, famous not just for their scenery but also for their rock art. Over 3,000 such sites have been discovered here, making this one of the best places anywhere to appreciate the 2,000-year-old artistry of the San people or Bushmen.

As tempting as it is to go off in search of cave paintings, I’m here with a rather different quarry in mind. Rhinos. I want to get up close and personal with them, and this seems to be the place to do it, with a healthy and well-protected population. We’ve all heard about the fate of rhinos in recent years – populations in freefall as a result of uncontrolled poaching, itself fuelled by the demand for rhino horn in traditional Asian medicine. Despite there being no scientific basis or proof (the horn is made of keratin, the same material as fingernails), the misplaced belief persists in some quarters that ground-up horn has special properties ranging from power as an aphrodisiac to a cure for hangovers and even cancer.

Today there are an estimated 30,000 rhinos of five different species left in the world, down from at least 100,000 half a century ago and still declining. Two Asian species – the Javan and Sumatran rhinos – are at the very brink of extinction, numbering less than 100 individuals in each case. The third type of Asian rhino, the Indian one-horned, is holding its own in a handful of protected areas. Here in Africa, both black and white rhinos were doing relatively well until the latest spike in poaching sent numbers spiralling downwards again. Then more recently came the sad news that Sudan, the last surviving male northern white rhino, had died in Kenya at the grand old age of 45.

Here in Matobo there are both black and white rhinos, the latter belonging to the southern race. The name is immediately misleading, for the whites are no different in colour from the so-called black species. ‘White’ comes from the Dutch word weid, meaning wide, a reference to the animal’s broad muzzle, designed for grazing on grass (black rhinos have a hook-lipped mouth, suitable for browsing shrubs). Yet it soon becomes clear that seeing any rhinos at all is not a given.

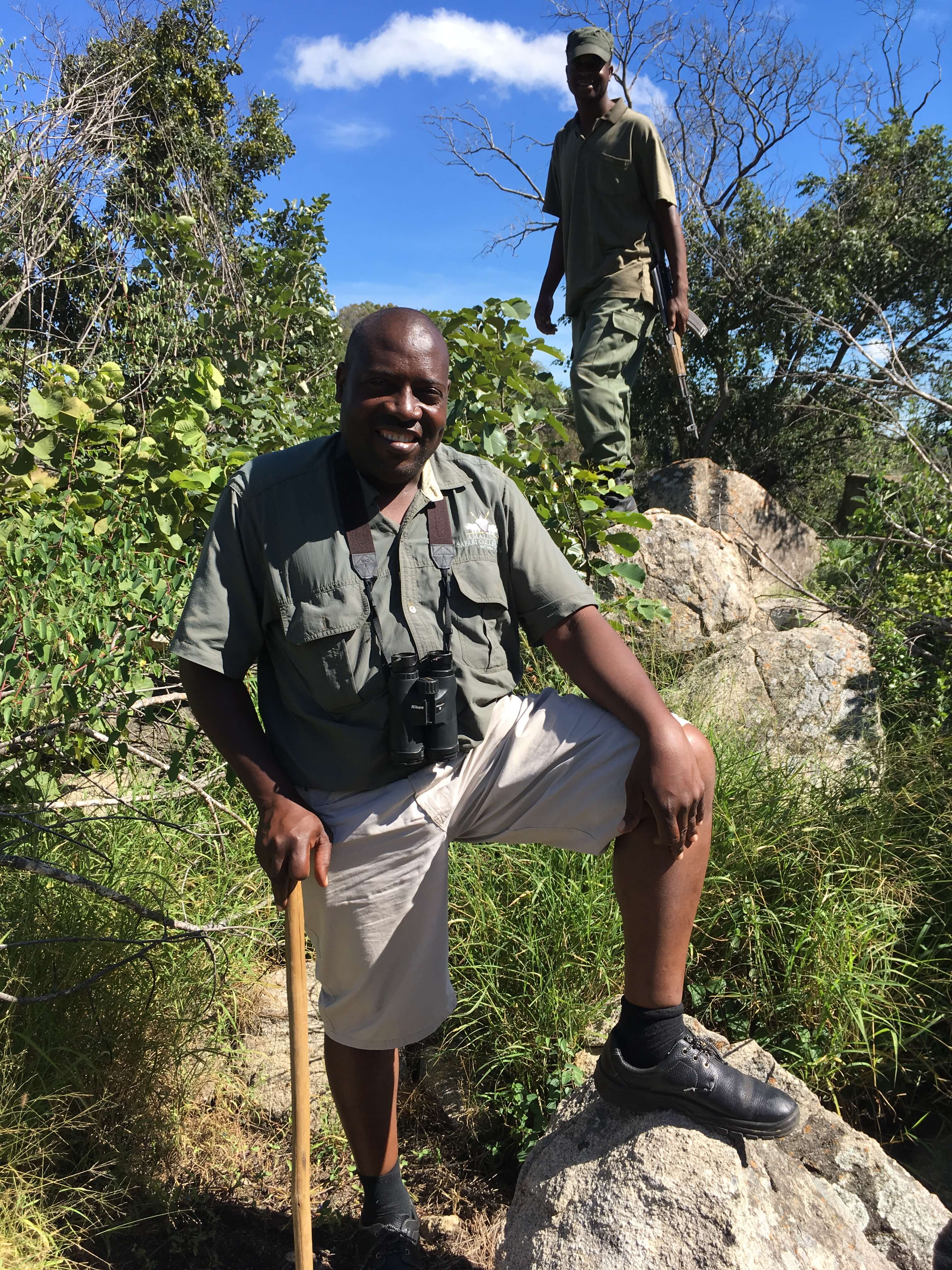

“First, you won’t be meeting any black rhinos,” says Howard Mlizane, a local wildlife guide with many years of experience and expertise in the bush. “They are secretive, largely nocturnal and prefer to hang out in thick scrub, which makes finding them very difficult. Also, they are notoriously bad-tempered and so very dangerous to approach.” Hmm, I’m beginning to wonder if this was such a good idea after all. Perhaps the whites are more reasonable? “Yes, usually but not always,” says Howard. I’m not exactly reassured.

Secrecy surrounds the number of rhinos found in the park, for the simple reason that any information on population levels might be used by poachers, which remain a very real threat. The animals are carefully protected by teams of dedicated rangers, two of whom we meet as we head off on foot on our rhino foray. Both are armed with rifles, a necessary tool of their trade. The risk of an unexpected encounter with wild animals is ever present, but in 2011 Zimbabwe introduced a ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy on poachers in response to an escalation in attacks on those protecting wildlife. The stakes have never been higher and rangers need to be able to defend themselves.

Under the supervision of Howard and the rangers, a small group of us walk quietly and slowly in single file off a dirt track and into the bush. We have been instructed to keep silent, with orders and directions given by hand signals. I’m paranoid that my mobile phone will ring and so keep checking it, even though I know it’s switched off. One minute the terrain is quite open, with grassy glades and even small ponds, then it’s closed again, and we are surrounded by vegetation. I keep looking all around, hoping to see something large and horned (preferably not too near but not far away either). We walk for about 20 minutes, the tension and expectation inevitably building, and then I nearly have a heart attack as a guinea fowl explodes out of the long grass at my feet. Everyone laughs, from relief as much as anything.

Then suddenly, Howard puts up his hand – the sign to stop. We are among bushes, and can’t see more than a few metres ahead in any direction. “There,” whispers Howard, “just there.” Frantically looking around, I can’t see anything except branches and large boulders. Suddenly a boulder snorts and wheels round to face us: an adult female white rhino. We freeze. She moves forward a few paces, straining to make us out through those famously shortsighted rhino eyes. Behind her, two more bulky shapes appear, as if by magic, out of the foliage: two rhino calves, one four years or so old, and one youngster of only 12 months. They sniff the air, and there’s a noisy salvo of huffing and puffing. Howard and the rangers have led us to this family group upwind, so the rhinos have not picked up our telltale scent. We stand, spellbound and rooted to the spot, as they meander slowly towards us, down to a range of only three metres. I’m so transfixed by the privilege of being this near to such rare and magnificent animals that taking a photo seems intrusive and inappropriate. I manage one or two shots though, and then suddenly the rhinos take fright and crash off through the bushes.

It’s one thing to protect rhinos, but who for and why? Compared to the situation in Zimbabwe a decade ago, when poaching was out of control in many areas, signs are now more encouraging. The main focus of the fight has turned to tackling the well-armed and trained poaching gangs who supply the international market in rhino horn, elephant ivory and other illegal products. Attention is also increasingly focused on conservation that is integrated with local communities and provides them with regular tangible benefits. “One can no longer consider animals in isolation from the bigger picture,” says Paul Hubbard, a Zimbabwean archaeologist and heritage expert who knows the Matobo Hills extremely well. “Effective wildlife conservation is impossible without considering the people who live next to or with the environment that tourists and conservationists come to experience, study or assist with.”

Tourism can play a major role in helping pay for wildlife protection and supporting local communities, although the ‘trickle-down’ benefits have traditionally been slow and often meagre. Once-in-a-lifetime experiences such as my rhino tracking can help bring a more meaningful injection of funds, along the lines of the already well-established gorilla eco-tourism in Rwanda and Uganda. Hubbard also sees important contributions coming from ethical and forward-thinking tourism companies channelling some of their profits directly into the areas where they operate. “Grassroots investment can make a huge difference to people’s lives and raise awareness of how best to protect the environment. Overall, I think the future for Zimbabwe’s rhinos and other wildlife looks brighter now than for many years.” It’s a thought worth holding as I slowly retrace my steps away from the magnificent slumbering beasts before me.

Images courtesy of James Parry and Getty Images