With a major new exhibition opening in Hong Kong, marking his first solo presentation in Asia, prolific young Colombian artist Oscar Murillo may be the darling of collectors but his ambitions aim far beyond the gallery walls, as William Rees discovered

It makes no difference what time of year it is, as Oscar Murillo’s studio remains a hotbed of activity regardless. The past few years seem to have been non-stop for the 32-year-old artist. As well as producing new work, he has been busy with exhibitions all over the world, including shows in his native Bogotá and his home town of London, and working both in his studio and in various other locales.

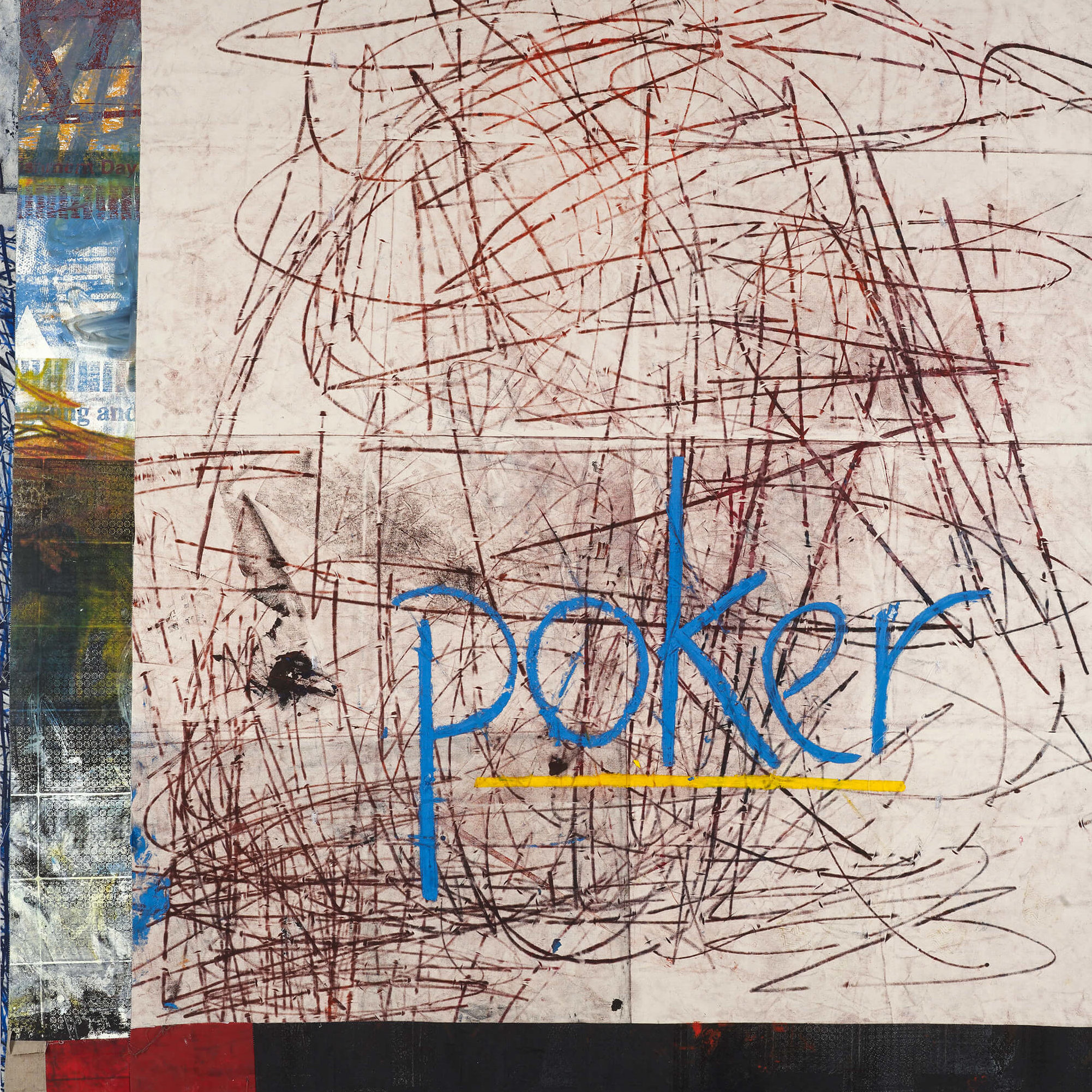

Murillo is perhaps best known for large, frenetic canvases, covered in scribbles, thick with impasto, dirt from the studio and large words scrawled across them. Pollo. Chorizo. Yoga. Painting, however, has always been just one among many of the media Murillo works in, with performance, video, drawings and printmaking also central to his practice. His most recent show, opening at Zwirner’s Hong Kong space, presents large-scale canvases that draw their inspiration from notations – mark making and recording he engages in during his frequent journeys (particularly in airplanes), on everything from sketchbooks to landing cards.

It was his frenetic paintings that first caught the attention of Don and Mera Rubell, collectors and early supporters of many now prominent artists, including Keith Haring and George Condo. In 2012 – the same year Murillo graduated from the Royal College of Art – the couple saw Murillo’s canvases at the Independent Art Fair, where he was showing with former gallerist Stuart Shave. Murillo was swiftly invited to partake in a five-week residency at the Rubell Family Collection in Miami. By then, he had also appeared on the radar of mega-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, and he staged a performance at the Serpentine Gallery in London later that year, as part of their Park Nights programme. The next three years aw Murillo exhibit at public art galleries (South London Gallery, The Mistake Room in Los Angeles, Art space in San Antonio), museums (MoMA), biennials (Venice, Ljubljana, Rennes) and commercial galleries (Eva Presenhuber, Marian Goodman) and at Yarat, in Azerbaijan. Now represented by two galleries worldwide – Carlos/Ishikawa in London’s East End and David Zwirner in New York and London – it seems Murillo’s meteoric rise has given way to a truly secure place within the international art community.

Within this international framework, for Murillo, local context, when making works, is instinctive. Born in the town of La Paila, Colombia, Murillo moved to the UK with his family at the age of 10. The many conceptual themes of his work – migration, globalization, labour and production, to name a few – are addressed on both a micro and macro scale with references to these wider issues alluding back to Murillo’s own biography. The most notable example is ‘A Mercantile Novel’, his 2014 exhibition at David Zwirner, New York, for which Murillo transported a working factory line and 11 empolyees from Colombina, the candy factory in La Paila that employed his family for multiple generations.

Recently, Murillo’s exhibitions have taken on the political issues of their locations. A 2015 exhibition in Madrid saw Murillo engage with the city’s current dialogue of protest by creating an installation of over 150 placards. (He had initially planned to stage an actual protest in the city, but the organizers immediately vetoed the idea.) Murillo is not trying to speak on behalf of anyone; he realizes that the issues he is dealing with are more complex than this. Instead, it is his background and position as an artist that allow for an honest engagement with the subject matter. “I guess because I too sit in between this duality of not exactly being this completed or fully Western subject, and so I have an awareness,” he explains. “There is an empty space I have to occupy, to see how my own concerns in my practice can infiltrate and immerse themselves into that new context.”

Elsewhere, a 2016-7 exhibition at Yarat came about after discussions with Suad Garayeva, Yarat’s curatorial director. Murillo decided to visit Sheki in the north-west of Azerbaijan. He tells me about the history of the town, which was once a stop on the Silk Road and continued production throughout the rule of the Soviet Union. I suggest there is some correlation between the silk factory in Sheki and Colombina in La Paila. “There are similarities,” Murillo agrees. “But what’s really sad is that since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the factory has lost its prosperity. The last time I visited, it was on the verge of shutting down. You could even say it’s lost its soul, in a way. But what is interesting is that, within that nostalgia, there is potential. Within this field of destruction and decay, there is the potential for something to… I guess in a filmic way, this idea of the phoenix rising from the ashes.”

The duality between the wider issues Murillo’s work addresses, and the finished look of the work itself, is something Murillo grapples with as an artist. “I’ve taken it upon myself to think about how the world works, while also consciously recognizing that I am an artist who enjoys aesthetics. How can I attempt to continue this dual existence between the pleasures of aesthetics within the context of painting, and the responsibility, the weight, of knowing these things? Being ethical, it brings in to question how one deals with that.”

It seems Murillo is increasingly drawn to the possibilities within these unstable materials. I refer back to that “phoenix rising” comment Murillo made earlier, and suggest that the use of the derelict factory material could be seen in the same way. “Exactly. You have the marriage of a utopian infrastructure, which is effectively dead, to a very small and humble system.” For Murillo, the potential of these materials is in what they symbolize – the memorialization of an industry that has ultimately broken down.

We go on to speak about Frequencies, a project set up by the artist in 2013. Working alongside members of his family and political scientist Clara Dublanc, Frequencies visits schools across the globe. Canvas material is attached to the desks of children aged between 10 and 16, where it is left for a semester. The canvases act as a journal of sorts, recording the thoughts and musings of the students.

Murillo takes me to the studio and shows me where he houses the thousands of canvases from the project. Italy, India, Kenya – one locality’s canvases look hugely different to another’s. Those from Kenya have a red patina as the school desks were outside and so are covered in a layer of dust from the clay landscape. Those from Singapore are very sparse, with some having barely been touched by the children. The project has also visited Azerbaijan, with canvases currently installed in two schools in Baku.

Frequencies was shown for the first time at the 2015 Venice Biennale, but Murillo explains that it is very much ongoing. “The project has just visited China, where it undertook its most extensive analysis of a country to date: 10 schools in six cities, with over 1,500 canvases installed.” Each canvas is uploaded to an online archive, and he plans to keep the material itself. His hope is that it will be used as a research tool for a multitude of disciplines, from art history and anthropology, to child psychology and educational studies.

Murillo shows me the tables from the Venice installation, a world map printed on each, with the locations the project has visited and their distance from the equator. I ask if he sees a link between the equator and the Silk Road. He nods. “The Silk Road tells you how certain trades moved from one country or one continent to another. The equator is a geographical reference point, but that then becomes political. If you look at how the world is divided, whether it is coincidental or not, it is strange. In the northern hemisphere you have these dominating societies, while in the south you begin to see a shift towards weakened power. However, this idea is slowly eroding.” Murillo has noticed this change in Colombia. “In the last few years, [Colombia] has suddenly evolved through tourism and trade. The moment you find yourself with a direct flight from London to Bogotá, you know something is happening.”

A version of this story featured in the Spring 2016 Issue of Baku magazine. Oscar Murillo’s exhibition, the build-up of content and information, runs from 19 September – 3 November at David Zwirner, Hong Kong

Portrait by Andrew Testa. Images courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Like this? Then you’ll love: Top five photographers from Uruguay you need to know | Oliviero Olivieri captures the remote mountain village of Xinaliq