Tahir Salahov is one of Azerbaijan’s greatest painters, renowned for his grim yet accurate depictions of life under communist rule. His influence and subversiveness extended across the sphere of Soviet art. Now 89, he’s still telling it like it is, says Caroline Davies

You are known, partially, for a trademark ‘severe’ style of painting. How did it develop?

In the Stalinist era socialist realism was the dominant style in art, but by the end of the 1950s I had a desire to depict true life, with all of its problems, with its difficulties and with a face – as I did in The Repair Men, Reservoir Park and Portrait of an Oil Worker. The oil worker looks sombre and only his red cigarette holder hints at some sort of optimism in life, against a background where everything is dark or black. The desire to show life as it gripped our imaginations – mine, and that of my contemporaries, artists Viktor Ivanov and Pavel Nikonov. Art historians have written about us being the founders of the severe style. This movement spread throughout the Soviet Union.

Your colour palette is often described as daring and intense, and splashes of red are considered your trademark. When and why did they first appear in your work?

My starting point is always the subject matter; it’s not something I make up, I paint it as it is. The Portrait of an Oil Worker, for example, was painted from life. He posed for me on the island of Artyom, near Baku, and that’s actually how he was. It was dark and his red cigarette holder stood out. If something makes me happy then I paint it. I try to brighten life up – in my portrait of the composer Kara Karayev, I painted a red folder lying on the grand piano.

It was in the 1950s that you began to realise some people saw your work as an affront to the Soviet system.

Yes. Just after I painted Portrait of an Oil Worker and Reservoir Park in 1959 they were sent to Moscow for an exhibition entitled ‘Azerbaijani Cultural Days’. It was there that I first received serious criticism of my work; I was asked why my paintings looked sombre and pessimistic. The Muscovites, the critics, the socialist-realist faithful all formed a circle and descended on me. Then every leader in the republic arrived at the exhibition – they came from the Ministry of Culture and from the Central Committee, and they all listened attentively. The mood was dark. At the time, I was the deputy chairman of the Union of Artists of Azerbaijan. The first secretary of the Union of Artists of USSR, Sergei Gerasimov, said to me, “Tahir, the reason they criticized you was because they could not see all that is in your works.” So he was the first to support me. By the beginning of the 1970s, everything became a bit more relaxed. We had needed a decade to get through it all.

Your work in the 1980s seems to have undergone a transition from severe to something more tranquil. Was this a conscious decision or a reflection of societal changes?

The subject matter was still the starting point of the work I was doing. If it was truly a joyful subject, then why wouldn’t I paint it as being just that? For me, it’s always about the subject, and this has been dependent on many things.

Over the years, you have also worked in stage and set design. How did this come about?

I started working in theatre in 1964, when Tofig Kyazimov – a director recently appointed to the Azerbaijan State Academic National Drama Theatre – approached me to work on the scenery in their production of Antony and Cleopatra. Kara Karayev wrote the music, Kyazimov directed and I produced the scenery. The play was a great success. Other plays I collaborated on with Tofig were Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Dzhafar Dzhabbarli’s Aidyn. I dressed Hamlet in a leather costume, which was criticized at the time for making him look like a motorcyclist. It was another 20 years before they adopted this leather costume in England! A few years ago, Andrey Petrov staged a production of 1001 Nights, with music by Fikret Amirov, which I also worked on. This ballet became part of the repertoire of the Kremlin Ballet Theatre. It has been staged many times; about 6,000 people have seen it. If I get this kind of opportunity, I don’t turn it down, because as an artist you usually work alone. When you work in a collective, it spurs you on and generates ideas and thoughts. I like working in a group. As to what pushed me into stage sets, I saw King Lear and Othello in Moscow in 1962, with Laurence Olivier in the main roles, and they made a huge impression on me. I wanted to reach the same level as those performances.

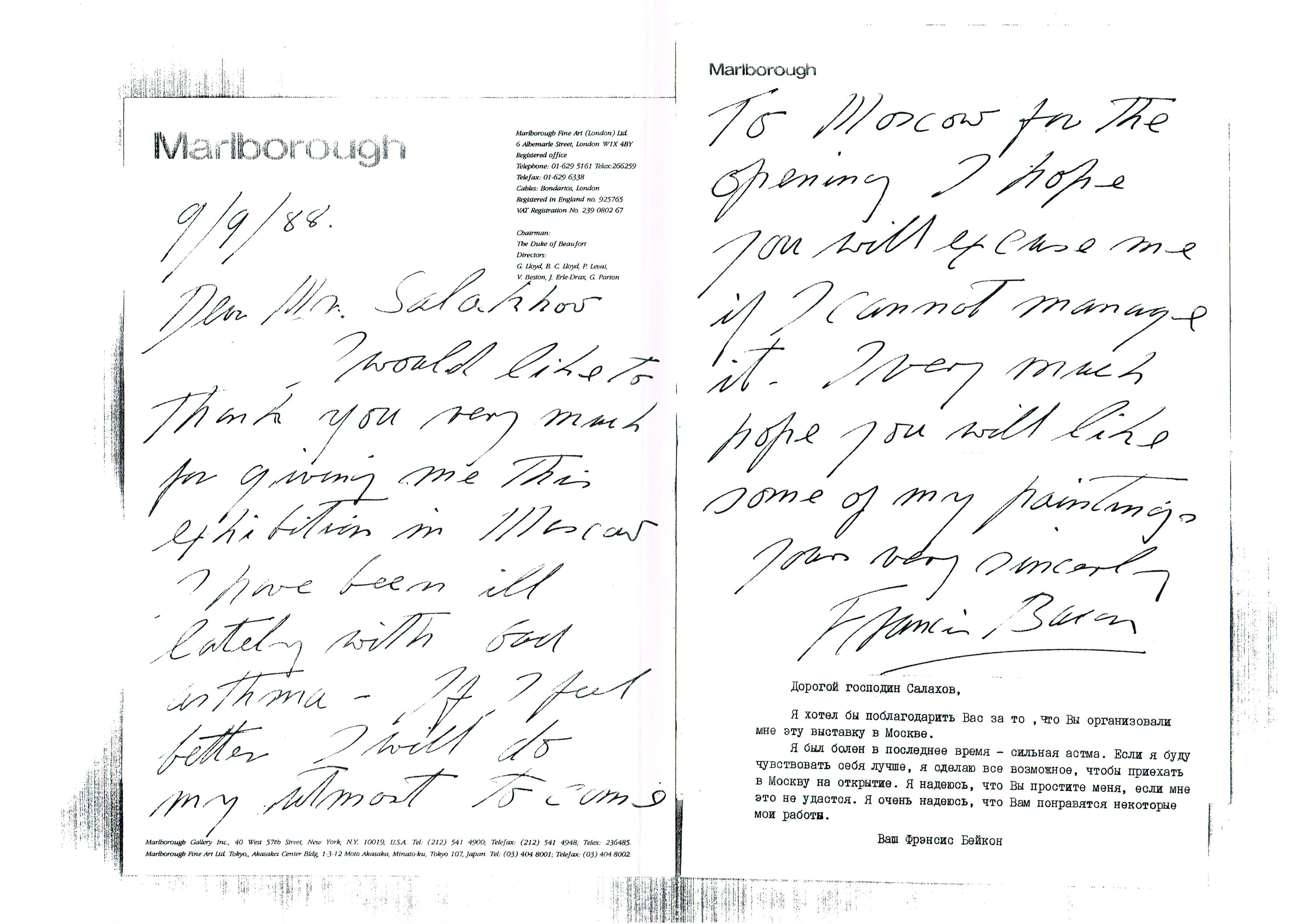

A handwritten letter to Salakhov from the artist Francis Bacon in 1988, apologizing for not being able to attend an exhibition Salakhov had organized for him in Moscow because he was suffering from his asthma. (Courtesy of the artist)

You and your two brothers all became artists in one way or another. Is there something that led you all along the same path?

In my childhood home there hung an etching in a golden frame. The previous owners had left it behind. Every day at mealtimes, we would look at this beautiful woman with flowing hair and her hands tied behind her back in chains. At the time, I thought it was Princess Tarakanova [a famous 18th-century Russian pretender to the throne]. I wanted to find out how it was made. That was the first thing. Then my father nurtured our potential with games and competitions. When he came home from work, he would give us [me, my brothers and my two sisters] some paper and pencils and say, “Let’s see who can draw [the war hero] Chapaev by the time I wake up.” Finally, two hours later, after we had been quietly working away, he would wake up and award one rouble for the best work. We loved this and it carried on for a long time. My middle brother, Mahir, took up calligraphy – he drew wonderful film titles and worked in a film studio. Sabir, my other brother, was a poster designer and painted images of space travel.

Similarly, when I was very young, a librarian gave me a book and said, “Read it and do some illustrations and bring them to me.” So, over a period of two months, I drew something, then took it back. She looked at me and said, “Well done! Here, take another book, read it and do an illustration.” It turns out she was saying the same thing to everyone – including Togrul Narimanbekov and Viktor Golyavkin [both artists]. She would collect our works and exhibit them at the library. That’s how I got to know Togrul. Keeping works on view fires the imagination.

The Old Town, Baku (1997). (Courtesy of the artist and the Research Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts, St Petersburg)

When did you first become acquainted with art?

An article was written about me titled ‘Tahir Salakhov started with asphalt’. In 1944, I was working as an artist in Kirov Park in Russia. Back then, in the difficult war years, I used to draw billboard posters and write public notices on the asphalt all over town. Or if a dignitary was coming to Baku, I would have to announce it by writing on the pavement, using oil varnish, as soon as the curfew had been announced, so that by morning it would be dry. A patrol would stand over me and watch me working for one, two, three hours. They would share food with me.

In the same year, the artist Vertinsky arrived in Baku for the first time after returning to the Soviet Union from China. This is when we got to know each other. I would open and close a stage set for him. This was also how I came to love theatre.

You have painted portraits of several of your contemporaries. Who had the greatest influence on you?

I have been lucky in life. My friends have included cultural figures who defined the face of Soviet times. These were remarkable people. I painted Kara Karayev, Fikret Amirov, the poet Sabir, the composer Uzeir Gadzhibekov – for me, it made no difference if they were dead or alive; it was always the creative idea and image of the person that mattered. I’ve always painted a portrait on impulse. One time, the composer Shostakovich called me. I traveled to his dacha and painted him there before he died. It was a poignant moment – he wanted to remain alive, not only through his music but also through a heroic image. I have many friends who played a huge part in my life – I wanted to measure up to all of them.

How has the art scene in Baku changed over the past decade?

Everything has taken a turn for the better. The Museum of Modern Art opened, the theatres were restored and the carpet museum was constructed. At a UNESCO event a few years back, Mehriban Aliyeva, the First Lady of Azerbaijan, showed traditional carpets alongside new carpets featuring my work, as well as pieces by Picasso and Joan Miró. I was so pleased. Azerbaijan is on a path to great prosperity.

Why did you move from Baku to Moscow?

I’m often asked why I left Baku. In 1973, I traveled to Moscow as a delegate with the USSR Congress of Artists. While I was there, the congress party gathered and began to nominate new board members. Suddenly, I was nominated for the position of first secretary of the Union of Artists of USSR. I protested, but they paid no attention to me. So I said, “Why didn’t you ask me this beforehand?” They said, “We knew you would refuse.” That evening Heydar Aliyev [then First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan] rang me: “Tahir, they phoned me. You know this is an honour for us. I made the recommendation – stay on and work!” And so I stayed. But every summer I return to Baku, so I can say I’ve never really left.

Venice, View from Balcony, Terminus Hotel (1999). (Courtesy of the artist and the Arbat Prestige Museum, Moscow)

What inspires you most when you visit a city?

An artist can always find an interesting phenomenon, an interesting angle, on what is new in a city and what links it with its past. Wherever I go, I’m always working. Any city has a huge effect on an artist. You have to see the morning, the sunny days, the overcast days and the city in the evening. Whether in Paris or New York, Rome or Baku or Moscow, there are endless subjects for artists. The most important thing is not to adopt an indifferent attitude; instead, approach everything with feeling, spirit and desire.

Do you think you will ever return to your homeland for good?

I’ve always been connected to Azerbaijan and its art. In a way, I have returned – I have a house in Baku as well as in Moscow. For me, geography is not important; the main thing is feeling love, solidarity. I always think about my childhood– it’s something that never leaves you. So I tell everyone, “I haven’t left!”

What are your goals and plans for the future?

I will continue to paint portraits of cultural figures, whose work I know well. I’m still evolving from work I began in the 1960s. And I will also continue my work on stage scenery. I want to dedicate one more canvas to the 20 January 1990 massacre – a tragic day in the history of Azerbaijan. I’ve collected material for this and I’ve started working on a sketch; I want this to be a major, serious piece of work.

How would you like to be remembered?

If just one of my works pleases someone then I will be happy. Have you seen the Mona Lisa hanging in the Louvre? Producing one good work is very difficult. Every artist strives to produce something good, something of beauty to leave for the public. Sometimes this happens, sometimes not. One of the leaders of our republic used to say, “I always value dedication in artists because artists are the most dedicated – he works silently, takes his work to a gallery in silence, they accept this work from him, or if not he takes the work and goes off quietly, and again carries on with his job. This is truly dedicated labor.”

In what direction do you think contemporary art is heading?

I’m in favour of modernity because it pushes mankind to discover new things. I painted To You, Humanity [depicting space travel] and exhibited it for the first time on 12 April 1961. It was on this very day that Yuri Gagarin first went into space. The painting measures 6m x 2m, and such a modern subject clearly caused excitement at the time. This work was recently exhibited in Vienna and Paris at UNESCO, where I met Tereshkova [the first woman to travel in space] and told her, “I thought about you, a woman in flight”. How could I have anticipated this? How could I have seen this? There are questions a contemporary artist can answer in their work. In China, traditional art lives alongside contemporary art and they rejoice in each other. They don’t focus on conflict, but bring enrichment. I’m all for taking art to new heights..

A version of this story featured in the autumn 2011 issue of Baku magazine.

Portrait by Tung Walsh. Images courtesy of the artist