Gavin Turk was one of the original Young British Artists. Now he’s creating public sculptures and turning to social projects. Opinionated as ever, he lets Francesca Gavin into his studio in East London

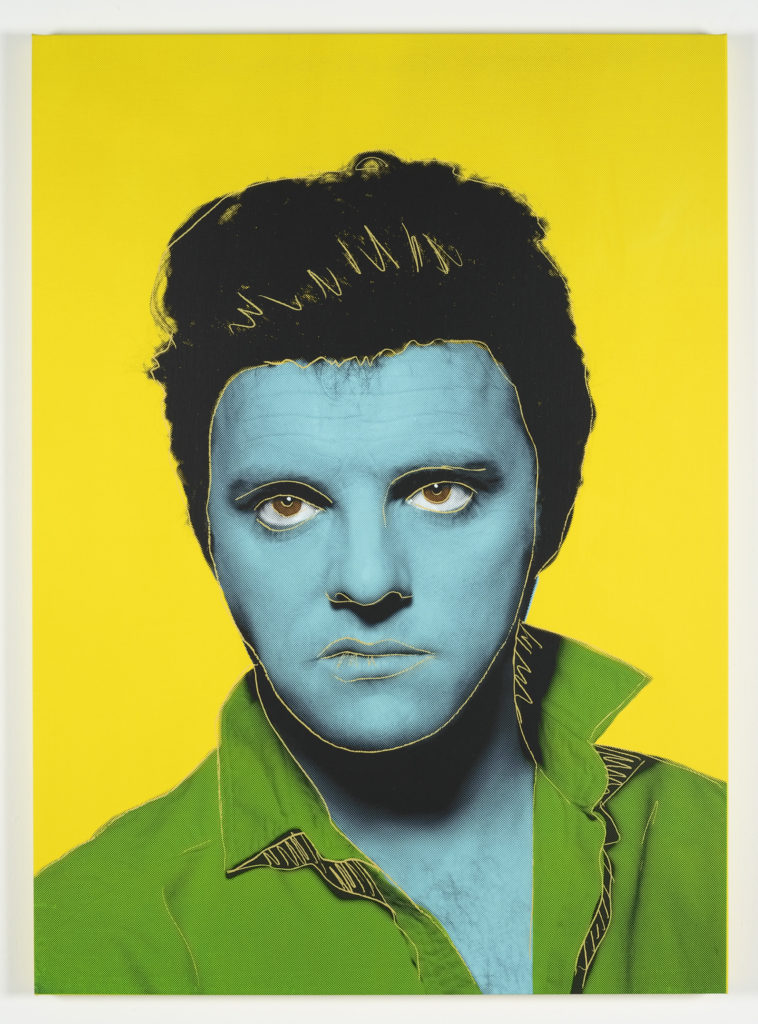

Hanging above the toilet in Gavin Turk’s studio is a small Lucio Fontana slashed canvas. In the hallway, there’s a little Van Gogh portrait and an Andy Warhol. Yet none of these pieces are what they seem. They are all works by Turk that play on the ideas of fame, perception and art history. Turk came to public attention in the early 1990s as one of the central Young British Artists or YBAs – the young guns changing the art world, one punk prank and confrontational artwork at a time. During his lengthy career, Turk has been one of the most consistently productive and provocative names in British art.

His studio is on the edge of East London, in the no-man’s land overlooking the Olympic Park in a black ex-garage with a red communist neon star above the door. Surrounded by dusty warehouses and quick-build high-rise flats, it could not be in a more desolate location. The building was formerly a place where people printed fake money and fixed knock-off cars. It’s a strangely fitting home for Turk – echoing the ideas of recycling, reinvention and fakery that are at the heart of his work.

In person, Turk is less confrontational and less chameleon-like than his work might suggest. When I meet him, he is wearing jeans and a white T-shirt featuring a black outline of an egg (a recurring motif in his work); he has a greying beard, a spark in his eye and a quick, sarcastic British sense of humour. Despite his success, Turk still has a hands-on relationship with art – even while I’m interviewing him, he’s creating a work on paper, surrounded by the mess of his studio.

In the past few years he has created a number of public sculptures – notably Nail (2011), a comic giant nail that sits outside the Jean Nouvel-designed One New Change shopping centre near St Paul’s in London. In 2014 he unveiled a bronze door entitled Ajar in the public gardens of a new housing development in Highbury, north London. ‘That was a real cast of the real door of the philanthropic project that became Action for Children.It was the door of the orphan home that was on that site before it was developed. A memory of the history of the space.’ Turk continues: ‘The difficult thing about working in public space – it’s open all the time. Quite often it doesn’t get looked at, because people think they can always see it another time. That it’s involuntarily there, in their face. There’s a strange point where making public sculptures is getting involved in an invisible activity. There’s something turned on its head about it.’

There is a generosity to Turk’s approach to art that separates him from many other YBAs. He is media savvy but comes across as open and natural. He is serious about art but he displays an impishness rather than the arrogance of some of his contemporaries. Turk is interested in a more collaborative vein of art. ‘It’s interesting the way someone like Jeremy Deller has become an important figure in the art world. People like Simon Starling; artists who are coming out of the gallery and working in a much more interactive way. It’s not the same sort of formal relationship between object and audience. I find it a rich seam for thinking.’

Turk shows a resistance to the mechanisms of the art world – even while he thrives within it: ‘I think it’s held to ransom by its industry – by its galleries, collectors and auction houses. There’s quite a stranglehold on the output. I’m interested in it – but it can irk me.’ His work is defined by its smart balance of humour, pop accessibility and art history. Originally as a direct reference to Jasper Johns’ painted bronze beer cans from 1960, Turk began to cast objects and paint them to resemble reality. ‘I like the idea that a bronze cast was, as much as anything, evidence of something having at one point existed.’ A cast liquorice pipe, with a nod to the Surrealist artist René Magritte’s famous painting, was followed by one of his most successful works – a filled black bin bag. ‘I had to question myself as to why the bronze sculpture was preferential to just putting a bag there. It seemed that by casting it in bronze, you somehow arrested time. The creases, folds, reflections, shadows – all became fixed. They became precious.’

Rubbish is a central motif in Turk’s art – in paintings, prints, sculptures. The bronze pieces are a modern twist on the ready-made – the Duchampian idea that an everyday object could be an artwork. The familiarity of his objects is unnerving. Unless you touched his bin bags, it was impossible to tell if they were real. ‘Suddenly you have to question everything,’ he says. ‘Suddenly it makes everything around you possibly not what you thought it was.’

Turk’s trompe l’oeil works have a sense of the abject – things you want hidden and thrown away, not necessarily shoved back into your life. As Turk notes, ‘[It comes] back to this idea of what’s real or not real, or what’s desirable or not desirable. What do we keep and what do we throw away? How do we edit? I kept finding myself drawn to things that people were throwing away, that the moment that something was thrown away was the moment that the value had left it.’ Turk’s desire to goad assumptions emerged early, when Charles Saatchi opened the seminal ‘Sensation’ exhibition in 1997 at the Royal Academy – the show that transformed the general public’ sinterest in modern art overnight. Saatchi exhibited some of Turk’s best-known works in the show, and as a tongue-in-cheek response to how the artists were being left out of the show’s opening private view, Turk smuggled himself into the RA dressed as a bum. ‘I had soiled, filthy clothes on. I stank of urine. I had a tin full of cigarettes that I’d picked up off the streets and re-rolled into rollies. It was a grim scene. I didn’t think what I was doing was art. Everyone was dressing up so [I thought] I’d just dress up as well.’ The well-heeled viewers at the glamorous opening didn’t know where to look. A year later he developed the idea of this liminal character who stood outside socialized society. ‘I started thinking this character – or this element within human nature or within a social structure – this character somehow created the frame, he started to delineate what was acceptable.’ Turk made a series of sculptures of himself as tramp figures. He followed this with a painted bronze sculpture of a curled-up figure in a dirty sleeping bag called Nomad (2003), and an empty sleeping bag piece entitled Habitat (2004). His aim was to touch on the audience’s desire not to look at a sleeping bag in the street, plus the Hello! magazine-style fascination to peak into people’s private spaces.

Provocation is at the heart of Turk’s work. ‘I think that it’s probably harder to be provocative now because people’s barriers are a bit more expanded. This was before computers entered into everyone’s house, and there were still underground threads of knowledge and information. I do think that art should be provocative. It doesn’t have to be crude. It can happen on a sophisticated level, but I do think it does have to enter into people’s subconscious or their preconceptions.’

Born in Guildford in 1967, Turk completed a degree at the Chelsea School of Art before doing an MA in sculpture at the Royal College of Art in 1989. From the minute he completed his degree show in 1991 he was serious art news. It was here that Turk famously hung a blue plaque – a historical marker that is found in public spaces in the UK, to commemorate famous individuals and where they worked or lived – in an empty studio reading: ‘Borough of Kensington / Gavin Turk / Sculptor / worked here / 1989-1991’. The RCA failed him and refused to give him his degree – but it got him the attention of Charles Saatchi and a young Jay Jopling, then starting the White Cube gallery. Frieze magazine, which launched the same year, printed his rejection letter as a point of public debate. Turk had arrived.

In the early 1990s, Turk continued with attention-grabbing works. He made waxworks of himself in the style of art-historical representations of famous characters: Che Guevara, Marat, Elvis. The most memorable was 1993’s Pop (later featured in Saatchi’s ‘Sensation’ show), a waxwork sculpture of Turk dressed as Sid Vicious, performing Frank Sinatra’s ‘My Way’, in the cowboy pose of Andy Warhol’s Elvis. The waxworks said everything about Pop Art, pop culture, pop music and fame. Turk’s play on celebrity couldn’t have been more timely, with British newspapers striving to make his generation tabloid rock stars. ‘[I’m] obsessed with the way art often becomes about storytelling or about media representations,’ says Turk. ‘There’s this constant attempt to try and make artists like pop stars or film stars or celebrities, but in a way they don’t really fit the mould.

Generally they’re not so media friendly. They use their art to communicate.’ Turk isn’t angry at being pigeonholed with his provocative contemporaries. ‘I think that the idea of the YBA movement was a strong and important one for giving artists [something] larger than a personal identity. I probably went in and out of it. I think what it did was allow you to talk about a certain kind of young, socially conscious art that was being produced at the beginning of the 1990s in the UK. It was a rough sort of carryall.’

In recent years Turk’s focus has turned to social art projects, including the Art Car Boot Fair, which runs annually in London. Here artists set up stalls, selling cheap art directly to their audience. Parties to coincide with Turk’s work are even part of his art-making process. For his series of sculptural busts, En Face (2010), he held ‘The Bust Party’, inviting people to come and deface and manipulate clay busts of Turk at his studio. The artist’s emphasis on free art, performative work and social projects led to his split with Jopling’s White Cube. As Turk explains: ‘I didn’t really want to be commercial and I was too slow to get on and make product. I think the gallery was not flexible enough to represent me in all the different ways that I was investigating the object. I was looking at art making as a performance or working with children.’

Turk had two children by the age of 28 with his partner Deborah Curtis – the first only two years out of his MA. Trying to balance that and still be part of the art world became important to him. ‘The art world was a different place. Private views were smoky affairs. There was a lot of beer. It was grown up. There really weren’t any children around. Deborah and I felt, socially, that people were missing out on the benefits of learning from children, as much as children learning from adults.’ The couple travelled to France, Germany and Holland looking at children’s museums and cultural spaces to engage children. They set up a crèche in their house for friends in East London, sharing the responsibility between parents. Curtis developed the idea of a children’s museum before their third child was born, and in 2005 the project was reincarnated as the House of Fairy Tales. ‘[It] was developed as a slightly Surrealist, quirky place where there’s a sort of adult-child interface and there’s excesses and there’s the idea of a place where creative play can be experienced on a profound level.’ The couple put on events at festivals such as Port Eliot and Glastonbury, and also at the Tate Modern and Whitechapel Gallery.

Turk has a constant energy to create and push his mediums. ‘Different mediums are like different languages. If I use different mediums I can talk in different dialects. I’m able to use syntax that otherwise I wouldn’t. It’s like each different material and medium has its own culture,’ he says. ‘You make another piece of work to correct problems you made before, things you didn’t say before. It’s almost like, as you make a piece of work you become a bit enlightened and realize other works you haven’t made. Art is a conversation.’

Turk’s art brings that conversation about recycling, re-imagining and layering to the fore – with his innate mischievousness. ‘I want to think about the idea of originality and signature and ownership and censorship. Your audience is able to register or recognize the fact that this is obviously not original. It’s a fake. That this is somehow an artwork in jeopardy.’

Photography by Ben Hopper; Images courtesy the artist and Live Stock Market

A version of this story appeared in the Autumn 2013 issue of Baku magazine.

See Gavin Turk’s work in the current group show, Proof of Life, running until 25 February 2018 at the Weserburg Museum of Modern Art.