The centenary of the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty and the advent of the Soviet state have prompted a slew of high-profile exhibitions in London and beyond. James Parry looks at what makes the artistic side of 20th-century Russia so compelling

It’s an understatement to say that the first three decades of the last century were a tumultuous period in world history. As democratic ideals pushed against autocracy and Europe sleepwalked into war in 1914, all sorts of writing appeared on the wall. The four years of conflict that ended with the armistice in November 1918 saw more than 18 million people killed, the subsequent redrawing of political boundaries across the central swathe of the continent (as well as in much of the Middle East) and widespread economic collapse. Equally dramatic was the toppling of the crowned heads of three major European empires: Austria-Hungary, Germany and Russia.

In Russia, the change at the top proved to be particularly profound. The end of autocratic Tsarist rule saw a short-lived provisional government and then the establishment of a Communist regime under Lenin. Every citizen felt the impact of such fast-moving events. “The revolution broke out willy-nilly like a sigh suppressed too long,” wrote Boris Pasternak through the eponymous hero in Dr Zhivago (1957). “Everyone was revived, reborn, changed, transformed. You might say that everyone has been through two revolutions – his own, personal revolution as well as the general one.”

Fabergé Cigarette case c. 1910. Gold gingko leaf, blue enamel and diamonds. A La Vieille Russie, New York

Art was profoundly affected by the social and political upheavals in Russian society, as the world’s largest country lurched from one extreme to another. Exactly what this entailed in terms of cultural and artistic output is brought into sharp focus by two current exhibitions at the University of East Anglia’s Sainsbury Centre, Royal Fabergé and Radical Russia (until 11 February 2018).

The first show examines the opulence and royal patronage that are synonymous with the exquisite decorative objects produced by maestro artist-jeweller Carl Fabergé. Among the jaw-dropping items on display are a diamond-studded stickpin given to ballet sensation Anna Pavlova after she had danced for the royal family at the Winter Palace, and exquisite enameled cigarette cases decorated in gold leaf and diamonds. One even has an old stub still inside.

The ostentatious wealth and lavish mutual gift-giving of the Russian royal family can be read now as one of the proverbial nails in their ultimate coffin. Also striking in this show are the close links between the Romanovs and the Saxe-Coburg Gothas, who ruled in Britain (and in 1917 astutely changed their German name to the much more British-sounding Windsor). King Edward VII’s queen, Alexandra (of Denmark), was the sister of Maria Feodorovna, Tsarina of Russia from 1881–94 and a regular visitor to the British royal country estate at Sandringham. She was doubtless influential in persuading the King to commission Carl Fabergé to create a series of portrait sculptures of animals on the estate for Alexandra.

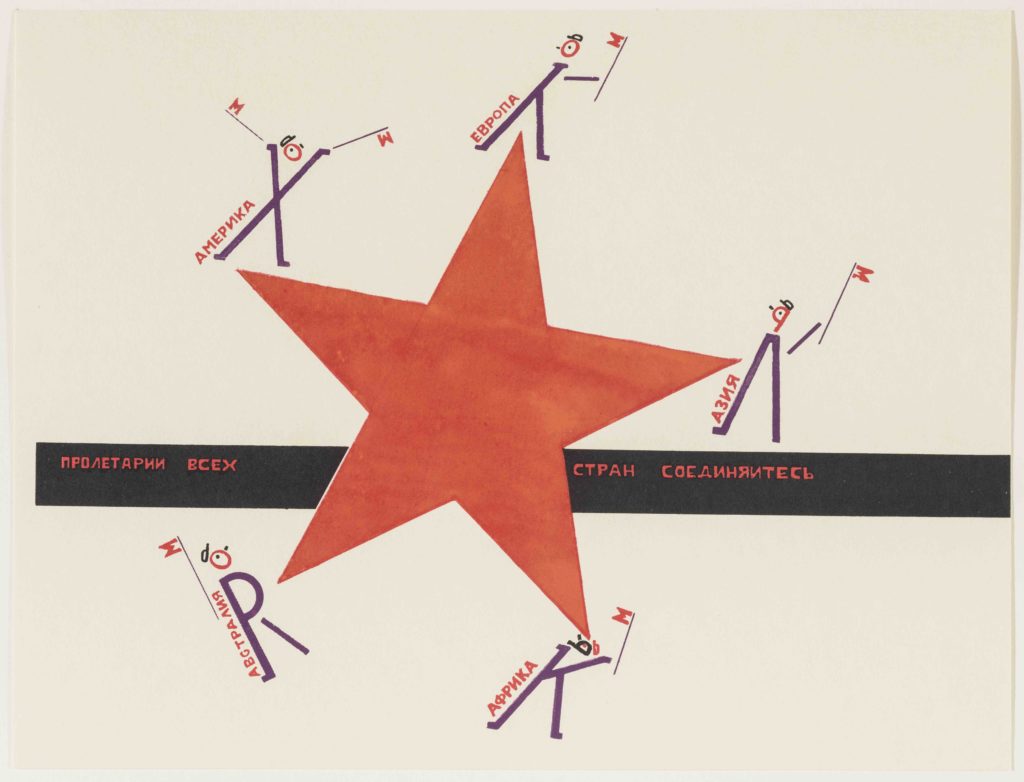

Detail from The Four Fundamental Ways of Arithmetic (1928) by El Lissitzky. Reprint 1976. Screenprint on paper (12 x) 25 x 32.5cm. Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands (Photography by Peter Cox, Eindhoven, The Netherlands)

The decadence of spending millions on bejewelled representations of one’s favourite pigs and chickens helps explain the events surrounding the subject of the second Sainsbury Centre exhibition, Radical Russia. Avant-garde artists were already flexing their artistic muscle in pre-revolutionary times, inspired by what they saw as the values of the honest Russian people in a forward-thinking patriotism that was to presage the upheavals of 1917. Figures such as Natalia Goncharova, Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky and Vladimir Mayakovsky used abstract forms in art, literature and theatre to challenge the status quo and help fuel an increasingly anarchic and subversive sub-culture in the dying years of the Tsarist age.

With the arrival of the Communist regime, the radical avant-gardists allowed themselves full rein – at least until the increasingly authoritarian Soviet machine clamped down on freedom of expression. Artists incorporated Bolshevik emblems such as the red star, hammer and sickle into energetic and imaginative works across a range of media, from book covers and porcelain to furniture and theatre sets. It was a brave new world and one that continues to resonate with art lovers several decades later.

“The unique vigour and creativity of Russian art and culture in the first decades of the 20th century makes it a source of lasting fascination in the West,” explains Radical Russia curator Peter Waldron. “Even though Stalinism pushed radical art deep into the shadows in the USSR, its influence extended far beyond the Soviet Union and helped lay the foundations for modernism across the globe.”

At Tate Modern in London, the exhibition Red Star Over Russia, A Revolution in Visual Culture 1905–1955 (until 18 February 2018) extends the story deep into the era of Stalin. Popular art designed to inform, educate and entertain the masses rapidly became a well-oiled propaganda machine, characterized by dramatic posters extolling the virtues of the Communist system and Soviet industrial might, as well as Russian art and culture.

Stakhanovites: A Study for the Esteemed People of the Soviets’ Mural by Aleksandr Deneika for the USSR pavilion at the international exposition in Paris, 1937. 1260 x 2,000mm. Oil paint on canvas. Perm State Art Gallery, Russia

The major centrepieces of the show are three oil paintings by Aleksandr Deneika, the original studies for a magnificent scaled-up mural in the USSR pavilion at the 1937 World Fair in Paris. The biggest work, Stakhanovites: A Study for the Esteemed People of the Soviets’ Mural, is being shown in the UK for the first time. “What’s so interesting about this painting is its social historical dimension as well as its pictorial strength,” says assistant curator Dina Akhmadeeva. “It’s an excellent example of how artists were called upon to produce works designed to activate the imagination of millions of people at home and also enhance the image of the Soviet Union abroad.” Sadly, Deneika was not given the chance to travel to France and never got to see the finished mural.

Lithography, photomontage and bold typography were used to particularly striking effect in Soviet era reproductions that still appeal hugely to modern audiences. Classic cinema posters of the 1920s are among the hottest such works right now, with one of the most sought after being Anton Lavinsky’s poster advertising the 1925 film Battleship Potemkin. An example sold at Christie’s in London in 2015 for a cool £45,000 (pardon the pun).

The glorification of the Soviet Union took on an increasingly hollow tone for many artists, as an increasingly repressive system forced them into a creative straitjacket. Right through until the 1980s ‘official’ artists were expected to slavishly follow the authorized style of Socialist Realism, with deviation from the party line likely to lead to loss of employment, housing or even worse. Running alongside the Red Star show at Tate Modern is Not Everyone Will be Taken into the Future (until 28 January 2018), the first major UK retrospective of Ilya Kabakov, who fled Russia more than 30 years ago and has since become one of the world’s leading installation artists with his wife and muse, Emilia. The show includes six full-room installations, including the iconic The Man Who Flew into Space From His Apartment, a masterful presentation of how the inhabitant of a cluttered room catapulted himself through the ceiling in a bid to escape – a metaphor for the suffocating and restrictive atmosphere of the Soviet era.

Desperate situations sometimes call for desperate measures. Art Riot: Post-Soviet Actionism, which showed at London’s Saatchi Gallery at the end of 2017, focused on the deliberately provocative activities of contemporary protest artists such as Pussy Riot, Oleg Kulik and Pyotr Pavlensky, who are continuing Russia’s long tradition of direct artistic intervention. The show also makes the point that protest and commentary can be articulated as powerfully through humour and thoughtful originality, as seen in Arsen Savadov’s Donbass Chocolate series and Natalia Yudina’s magnificent fluffy bust of Lenin, both of which bring a particularly Russian spin to the artistic dice.

Whether it’s gilded gifts from the last Tsar, cleverly crafted Soviet propaganda exhorting the masses to work harder, or a more contemporary commentary on the present state of Russian society, there’s no denying that the artists of the largest country on the planet never shirk from confronting the world around them in direct and innovative ways. The next century is likely to bring as many challenges as the last, but the diverse creativity that is integral to Russian culture will surely prompt an equally exciting artistic response.