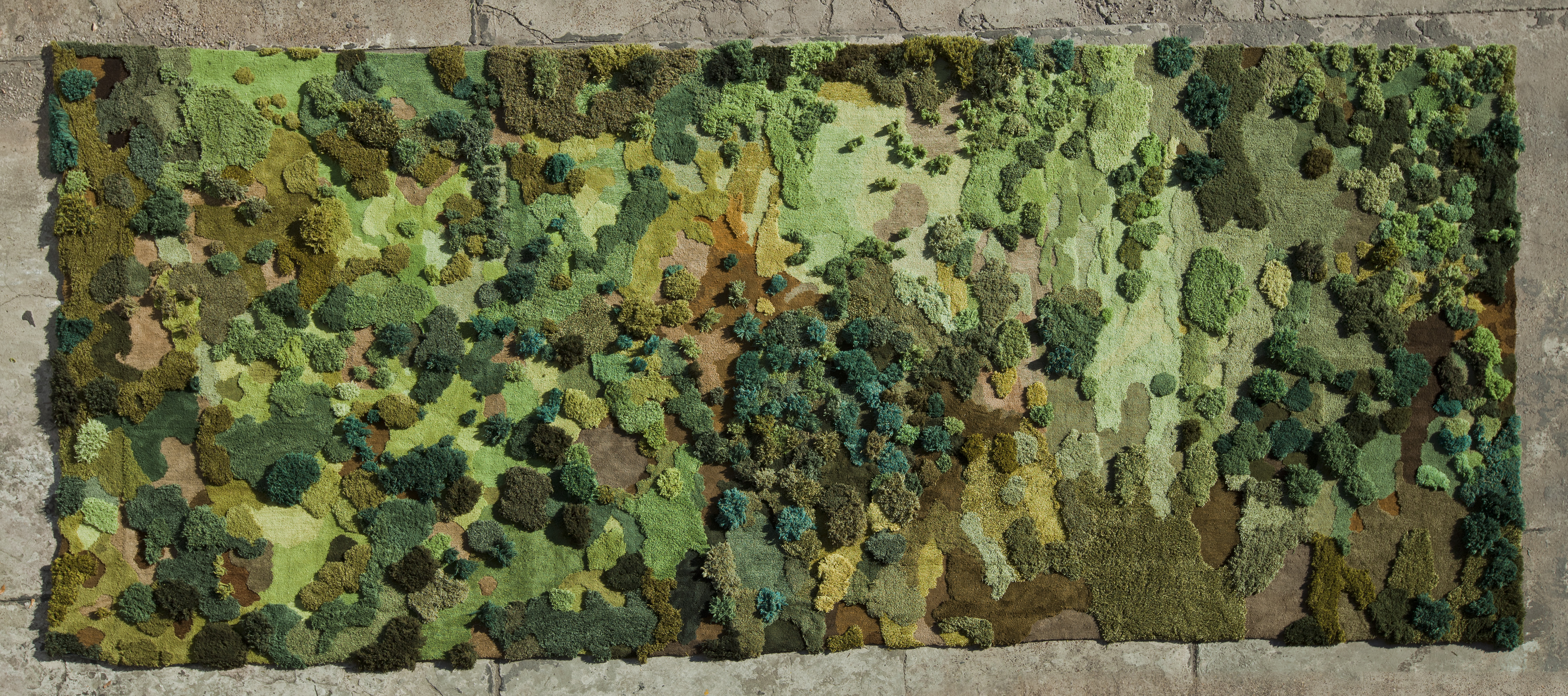

Argentine artist Alexandra Kehayoglou creates vast carpet installations that call to mind the verdant textures of the natural world. The works are a testament to her love for the land and her drive to preserve the natural world through conservation. With her latest work featured in Hannah Ryggen Triennial: On borders, place identity and human worth currently on view at the Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum, Baku speaks to the artist about her process and the creatives who inspire her work

Your carpets are vast installations that mimic mossy, grassy textures from around the world. How did this start?

I started working with carpets because it was a familiar medium. I started experimenting in the family factory. I was finishing art school at that time and I had an urge to include these materials in my works. They were the resources available to me and it was an opportunity to put into use something that was just standing there. My father has been an inspiration in this sense; he encouraged me to do something with our unused, surplus wool. I also think that something deep inside drew me to do so.

The process is something that is constantly evolving. I work mostly with landscape and sites that are on the verge of disappearing, changing due to human impact.

How are you able to imbue so much meaning and emotion into carpets?

Textiles carry information. Threads are like veins, or bridges or cables, they carry this faculty inherently. From the very start, the process of creating – the drafts, the design and the production – is a very conscious work. I am very selective, especially when it comes to the energy that surrounds the making of a project. The landscapes I choose to reproduce are not random. There is always an intention when we tuft. We put this intention into the making; it’s like a mantra or a prayer.

What is the biggest challenge in working to such a large scale?

Time is a big challenge. Large projects require study, drawing, solving technical difficulties, and overcoming new challenges for each work. My work is all hand-made so it is very hard to speed it up, and the world seems to always ask for new work! One year is not enough time to work on a large-scale piece. Another challenge is weight. Carpet works get very heavy and we have to move, roll and then transport them.

You were born and live in Buenos Aires, Argentina. How does your hometown inspire you?

I live just by the city. I am inspired by the way nature makes its way through. I live in a country where the norm is to exploit our natural resources: agriculture, farming, mining. Our government sees the use of our land as a means to make our country big again. Argentina was el granero del mundo, “the barn of the world”. This point of view is entrenched. Working with the land allowed me to connect with the aboriginal communities, Tehuelches and Mapuches, who have always had a different relation with the land. They take care of it, they actually have a relationship with it. Ironically, they are portrayed as terrorists, since they are against the exploitation of nature.

How does your passion for conservation feature in your work?

As I said before, I imbue my work with an intention – a prayer. At the studio, we put love into the work, it is surrounded by a positive energy. When I reproduce a landscape, my intention is to eternalize it, but the carpet brings new meaning. They are interactive works, they invite you to sit, to stop, to lie. You adopt a different perspective that has to do with the land.

Your piece, Prayer Rug, features in the Hannah Ryggen Triennial: On borders, place identity and human worth, to create a dialogue with Hannah Ryggen‘s political tapestries. How does Prayer Rug complement Ryggen’s work?

Seeing the prayer rugs next to Hannah Ryggen‘s brought a new perspective to the works which I have not seen before. Quite apart from the aesthetic discovery of seeing my work together with such masterpieces, you could see how they each reference different problematics and the dialogue between the works – and the activist element of the prayer rugs was highlighted.

Which of your works are you most proud of?

I think it is the work I made last year in Rome What if all is, for the exhibition Dream curated by Danilo Eccher. This work is very large and complicated since it is a depiction of a cave within Bramante’s steps at the Chiostro in Rome. It has different landscapes, textures and colors, and it tells a story about memory, rock paintings, and the disappearing tribes from Patagonia. In many ways this work challenged my own limits as an artist. I recently visited it again, months after the opening, and it felt strong.

Which artists or thinkers inspire your work?

Violeta Parra, a Chilean songwriter and artist. She worked with tapestries too, and had a very difficult life fighting for her beliefs in Chile. She is a huge inspiration for me as a woman from South America talking about land and memory issues, from within a very conscriptive regime that believes we must exploit the land for our own benefit.

I am also inspired by my partner, Jose Huidobro. We work together and he has his own studio but my work is constantly affected by him, as well as thinker Rodrigo Cañete, an Argentine critic who also writes an art blog. We discussed my work a lot and he has a big influence on how we think about the role of contemporary art in the new art and political scene.

You collaborated with Dries van Noten (main image) in 2015 and with Hermès this year. Craftsmanship and tradition is experiencing a huge revival and offers an antidote to modern life. Is artisanship here to stay?

Artisanship never really left. It might have been seen as a “lower” kind of art, but it has travelled through history, with old techniques getting passed on. Now traditional techniques are incorporated alongside new techniques and it is all works brilliantly.

What are you working on next?

I am working investigating a place called Lago Salitroso, which I first studied for the Hannah Ryggen Triennial in Trondheim, Norway. These places are not only special landscapes, but there is a relationship with memory and disappearance that are topics that start to appear within my work.

Also I am working on my first monograph that will hopefully get published this year, or 2020 at the latest, by Buchhandlung Walther König. I am very happy to work with art historian and editor Cornelia Lauf and the designer Luc Dyrke from Delf, Belgium to pull the book together.

Images courtesy of Alexandra Kehayoglou