Like a fish to water, conservation project manager Rory Moore was born to better the world’s oceans. Here, he talks to Sophie Breitsameter about his breathtaking underwater photography, Blue Marine Foundation’s latest projects and Moore’s childhood moments that got him hooked on conservation

“My earliest memory of the sea was in Pembrokeshire, Wales. I must have been six. My uncle, who is a marine biologist from California, and thus my hero, was visiting, and we were scouring rock pools for ‘specimens,’” says Rory Moore, senior project manager at Blue Marine Foundation, when we meet. His eyes light up: it is no surprise that the ocean became his calling. “We came across a shark egg case attached to some seaweed that had washed ashore. I vividly remember holding the egg up in the sunlight and watching the baby shark swim around inside the egg in front of our eyes. From that day on, I was well and truly hooked!”

Hook, line, and sinker, Rory has since managed projects in the Maldives and Mexico and spent three years in Indonesia working on a research project. When he was younger, he spent his summers in California and winters in Wales, developing a passion for conservation on two sides of the world. “I have always been a keen fisherman and would spend hours on the riverbank trying to catch elusive trout, salmon and grayling. To catch a fish, one first has to understand its ecology, so I would learn everything about their diet, habitat and biology. This curiosity and the collection of available knowledge inevitably led to a great passion for fish. I often return to the California mountain lakes and Welsh rivers to fish: it motivates me to keep working in conservation,” Moore explains.

Following his years spent designing and managing marine conservation projects internationally, Rory joined the Blue Marine Foundation. Blue Marine Foundation (also known as BLUE) is a charity dedicated to creating marine reserves and establishing sustainable models of fishing. It was started by the team behind the acclaimed movie “The End of the Line” in 2009, which examined the devastating consequences of overfishing and the unregulated fishing industry.

BLUE’s mission is to place 10 per cent of the world’s ocean under protection by 2020 and reach 30 per cent by 2030. With projects across the globe, today we discuss their recent work in Azerbaijan.

In 2018, Azerbaijan announced the creation of the first Marine Protected Area in the Caspian Sea, the largest inland body of water on the planet. Located near the mouth of the Kura and Aras rivers, it will aim to protect six significant marine species on the brink of extinction, including the Caspian salmon and the Beluga sturgeon.

Tell us more about the Azerbaijan project.

Azerbaijan was the first ever project that I visited with BLUE back in 2015. We drove to the Ghizil-Agaj wetlands, an area known for its migratory populations of water birds. Immediately, I saw the area’s importance for the critically endangered, Caspian migratory fish. The shallow sheltered waters provide ideal conditions for juvenile sturgeon as they acclimate from freshwater to the marine environment. Caspian kutum rely on the brackish waters for spawning, and adjoining river systems are crucial for migrating Caspian salmon. Protecting Ghizil-Agaj and creating the first Marine Protected Area (MPA) in the Caspian is a step towards the recovery of some of the rarest and oldest fish on the planet. The MPA designation is also a great example set by Azerbaijan in the region. We hope other Caspian coastal states will follow suit and create MPAs of their own, building a network of marine refuges throughout the region. I would like to see 30 per cent of the Caspian Sea protected by 2030.

How is BLUE working towards its mission?

BLUE’s strategy is to focus on places that have a chance and make them better. Britain is responsible for 6.8 million square kilometres of ocean — the fifth-largest marine estate in the world — the vast majority of which is around the UK’s 14 Overseas Territories. BLUE remains engaged in the creation of protected areas around St. Helena and Ascension Island. We hope to achieve a marine reserve in all of Ascension’s waters: that is 440,000 square kilometres of ocean where industrial fishing would be banned! A great breakthrough was to see the UK government announce a target of 30 per cent of ocean protected by 2030, aligning with BLUE’s long-term strategy.

What’s next?

The high seas — the parts of the ocean beyond national jurisdiction — make up nearly two-thirds of the world’s ocean. Yet less than one per cent of the international waters is properly protected. Protecting the high seas is vital to achieving the goal of 30 per cent global marine protection.

I have been spending a lot of time in the Mediterranean, designing a regional programme that will create sustainable, small-scale fisheries within a network of properly managed MPAs. The target is the same: 30 per cent of the Mediterranean protected by 2030.

What’s going to be centre stage in the conservation world this year?

Hopefully, 2019 will see the designation of some of the largest MPAs on the planet. These great ocean refuges will allow some fish stocks to recover. Yet, the demand for wild fish is growing: not only for human consumption, but to feed farmed fish, which, for the first time ever, accounts for 50 per cent of fish consumed globally. Depleted oceans lack the natural “immune system” or resilience to other pressures like pollution and climate change.

Ocean conservation is not just a matter of protected areas. Innovation is becoming increasingly important, whether providing non-fish-based sources of protein, reducing plastics on land and at sea or restoring seagrass beds, which capture atmospheric carbon at a rate five times faster than tropical forests.

What areas of conservation are you particularly passionate about?

The same Californian uncle had a sturgeon farm near San Francisco, where I would spend my summers. I developed a great fondness for these fish. Sturgeon are the most endangered group of species on the planet and will become extinct in the wild unless conservation efforts are successful. This is where my passion lies, and I happily would — and likely will — spend the rest of my life trying to restore healthy populations of sturgeon in the Caspian Sea.

Your underwater photography has been recognized internationally. How would you describe the experience of being so close to these extraordinary animals?

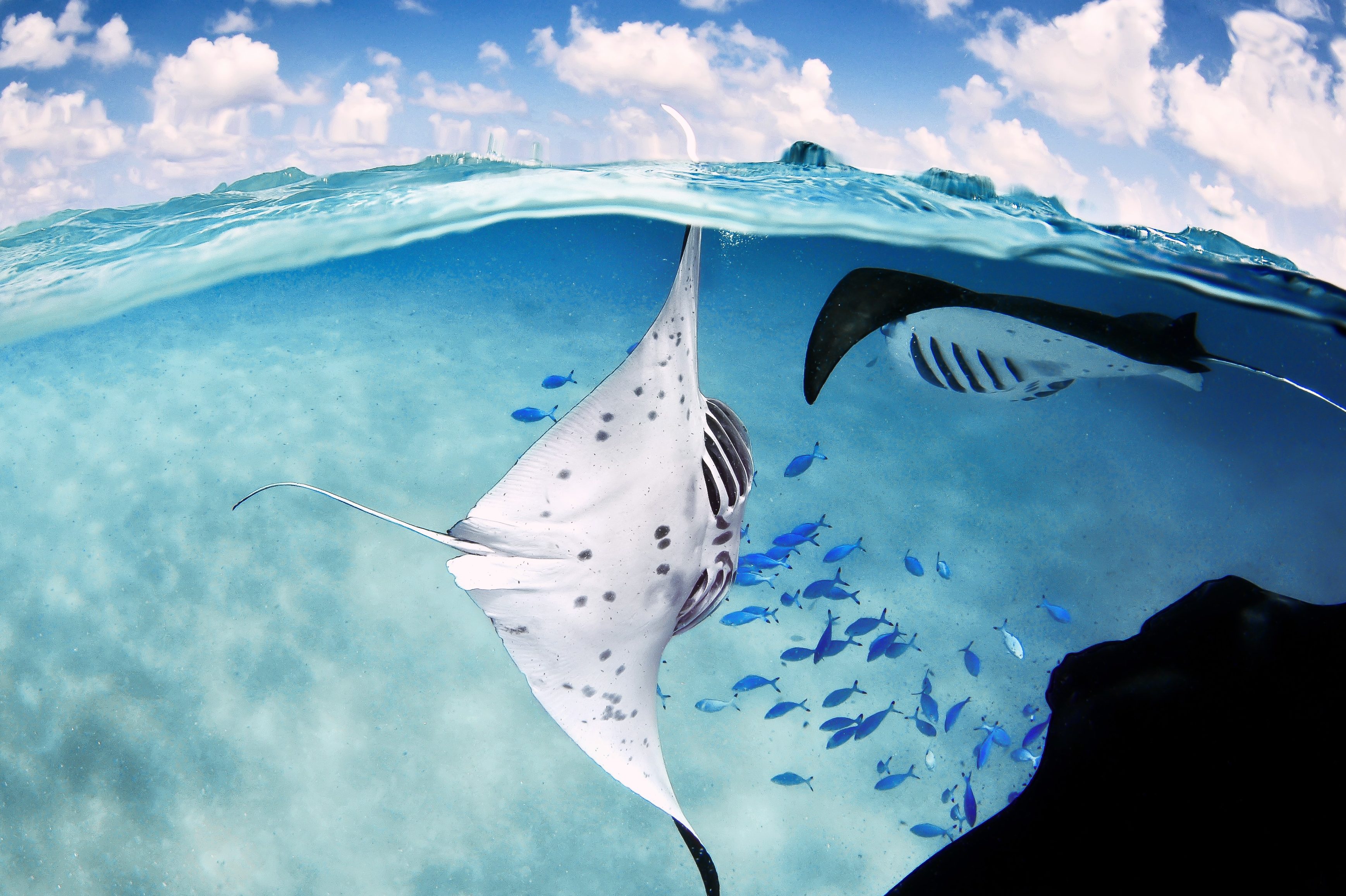

Sometimes it’s exciting, sometimes it’s exhausting and sometimes it’s quite terrifying… But it’s never boring! There is often a strange disconnection between the photographer and the subject when separated by a lens. For this reason, I would occasionally leave the camera on the boat and go free-diving. I would usually regret it. I suspect the trickiest photographs I’ve taken are split-level, capturing underwater and above. Focus, light, timing, drops of water on the lens and the need to breathe all make this type of shot quite difficult to perfect. I never did.

Can you tell us about a photograph that you are most proud of?

I spent months photographing manta rays in Hanifaru Bay in the Maldives. The small bay would fill with plankton and manta rays, and whale sharks would come to feed. One day I got too close to a big female manta and she hit me hard in the chest, smashing the camera out of my hands. Completely my fault. I caught my breath and swam down after the sinking camera. I got it, just, and swam into shallower water to take a rest. Just then, this “scene” constructed itself in front of me and I took a shot — probably the photograph that I am most proud of.

What has been your most memorable conservation project to date?

Some 300 miles west of the Pacific Mexican coast lies the Revillagigedo archipelago. The islands are home to giant manta rays, a distinct and larger species than the Maldivian reef mantas. I was sent to the islands in 2009 to try and discover where the mantas were migrating each year. If we could answer that question, we could propose effective conservation measures for the population. We used acoustic tags to track the rays, each tag carefully inserted into the six-metre-wide rays as they swam by. I have never been so nervous, desperately trying not to injure the animals or lose the tags. In the end we managed to tag around 15 individuals, and the results showed us that the mantas were indeed moving vast distances across the ocean to the islands. The Revillagigedo Islands were declared a marine reserve and national park in 2017, and the population of giant mantas is now well protected.

How can we get involved?

It is important to learn about the fish we eat and where it comes from. Is it endangered? Is it certified as “sustainable”? Is it the right season? Where does it come from? Who caught it? Most of this information is available with a bit of hunting. The Marine Stewardship Council website is a good place to start. Volunteering on conservation projects, spreading awareness, improving our knowledge of the environment around us are all things that will create a global empathy for the planet.

Images courtesy of Blue Marine Foundation and Rory Moore

BLUE exists to combat overfishing and the destruction of biodiversity — arguably the largest problem facing the world’s oceans — by delivering practical conservation solutions, including the creation of large-scale marine reserves. BLUE’s aim is to put 10 per cent of the world’s oceans under protection by 2020 and 30 per cent by 2030. We also work to establish sustainable fisheries, allowing fish stocks to recover over time. For more information, please visit bluemarinefoundation.com