The most influential architect of modern times, his closest confidante, and a curiously recalcitrant city authority. Peter Popham explores the true story of Le Corbusier’s greatest legacy

Surely the greatest architect of the 20th century deserves no less: a museum dedicated to his life’s work, designed by himself, executed precisely according to his wishes, and occupying a prime site in the biggest city in his homeland.

Yet the history of the museum, which Le Corbusier called La Maison d’Homme (renamed the Pavillon Le Corbusier, as of May 2016), has been a long and bitter struggle between the woman who conceived it and brought it to completion after his death – a designer and collector called Heidi Weber – and the Zurich city authorities. Where one would have expected a happy collaboration with the shared goal of honouring one of the most remarkable men in modern history, instead there have been decades of conflict, bad feelings and attrition. The museum has stood for decades, immaculately maintained and a fitting tribute to its architect; but except on special occasions its doors were mostly closed to the public. When its lease recently expired after 50 years, Weber was evicted, and it is now owned by the city of Zurich. Weber remains unhappy with the way she and the museum have been treated, and the longstanding failure to make the most of what should be a major asset for the city for so many years is baffling. What went wrong?

Heidi Weber in the basement of the museum Pavillon Le Corbusier, formerly known as La Maison d’Homme

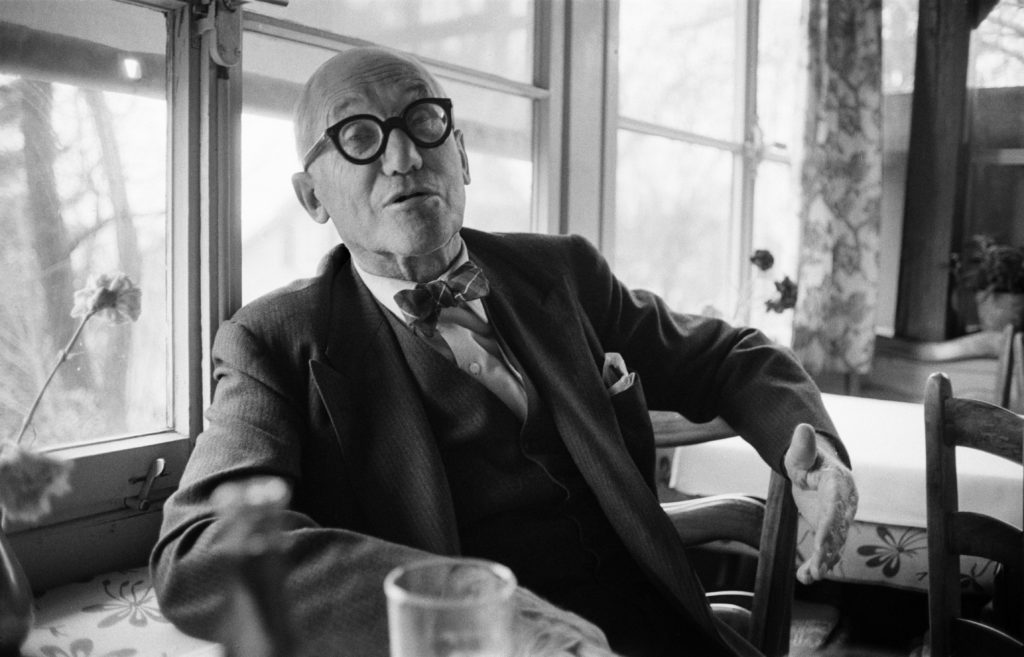

Le Corbusier was the man who redefined the urban landscape around the world. From São Paulo to Moscow via Paris and London, the utopian modernism visible in sweeping cityscapes of tower blocks, concrete and glass walkways all owe their genesis to the revolution Le Corbusier begat in architecture. When he met Heidi Weber on the French Riviera in 1958, he was already the most famous – infamous in some circles – and influential architect in the world, unmistakable in his striped bow tie and owlish black spectacles. Weber was a furniture designer with her own modernist atelier in central Zurich; she “discovered Corbusier through his writings,” she said, and fell in love with his paintings and graphic work, his furniture and his architecture.

Her single-minded devotion to his legacy for half a century has led many to suppose that they must have been lovers. One year after the death of Yvonne, his rather wild, alcoholic wife of 35 years, there was certainly a vacancy in his life, and Weber’s own marriage had ended in divorce many years before. But Weber firmly denies the gossip. “People always talk,” she says. “If I had been his lover I would have said it, I would not have been ashamed. But it would have been a lie. The problem of people saying that is that society wants to undermine the work of a woman: to say that they are only capable through the bed, no? We had a friendship and a working relationship.” The relationship began with his paintings, which she greatly admired, and progressed to his four revolutionary tubular steel chairs, which she displayed in her Zurich atelier, Mezzanin. But its consummation came with her idea of building a museum dedicated to his work on a prime piece of Zurich real estate, on the shores of the city’s lake.

The architect took some convincing. Though Swiss by birth, like her, he had taken French citizenship many years before. Despite being world famous, with many buildings realized from Paris to Chandigarh in India to Tokyo, his stature was slow to be recognized in Switzerland: “No man is a prophet in his own land,” as Weber remarks. Four plans for buildings in Zurich during the 1930s had come to nothing, leaving him frustrated and bitter. So his response to Weber’s museum proposal was tart. “No, I won’t do anything more for the Swiss,” he told her. “They have never been nice to me.” When she persisted, he warned her: “You are going to have problems with your Swiss.” No truer word was spoken. Yet at the beginning, Weber’s determination swept all before it. The city’s social democrat mayor, Emil Landolt, wrote to her enthusiastically soon after the project was conceived. “I want to inform you that I strongly approve of your idea of building a Corbusier structure [on the lakeshore],” he declared. In 1963 Weber signed a contract with the city of Zurich, granting her a lease on the planned building for 50 years, after which ownership would revert to the city on payment of 70 per cent of the investment costs, which at the beginning were to be borne entirely by her.

The contract came into force in 1964. But the first of many shadows to fall on the museum was already present. Next to the site allotted for the museum was a white-painted clapboard structure called the Haller Atelier, containing works and the archives of Hermann Haller, a Zurich sculptor. In his plans, Le Corbusier required that building to be removed, making space for a visitors’ car park and allowing the museum’s approach path to arrive directly at the front door. The demand did not seem unreasonable: the atelier was only a recent and provisional occupant of the site, having moved from another location. According to Weber, “Le Corbusier was verbally assured by the city councillors… that the rental agreement… would be terminated, and the studio relocated or demolished.”

This undertaking was repeated in a letter to her from the city in 1966. But after influential figures in Zurich’s cultural life, including the legendary novelist Hermann Hesse, signed a petition in 1967 demanding that the atelier be preserved, the city backed down. That U-turn set the tone for the dysfunctional relationship between Weber and the Zurich authorities, which has prevailed ever since.

Le Corbusier died of a heart attack while swimming in the sea in 1965, aged 78. Two years later, after bruising disagreements with the architects appointed to finish the job, three of whom Weber sacked after they tried to modify details of the original design, the Centre Le Corbusier was officially opened by Weber before a distinguished audience of architects and friends. She had sold her home and practically everything she possessed to bring it to completion; when money and credit finally ran out, she rescued it by auctioning some of her Le Corbusier paintings at Sotheby’s. But its initial success justified all the sacrifices: when it opened its doors to the public, 2,000 visitors streamed through, and in the first year 45,000 people from all over the world came to see it. The museum seemed set to become a big success and an illustrious addition to Zurich’s cultural skyline. But problems latent in the original contract soon made themselves felt. It was inconceivable that a museum such as this, with high running and maintenance costs, could make a profit, but nothing in the original contract obliged the city to contribute to its costs.

By 1970 the museum was an established, undisputed success, with visitor figures in the thousands, but Weber could only continue to run it by selling off what remained of her collection of Le Corbusier paintings – something she refused to contemplate. To get her and the museum out of this fix, a number of high-profile Swiss rallied round, including the internationally renowned artist Gottfried Honegger and Max Frisch, author of celebrated plays such as The Fire-Raisers. They formed a patronage committee and launched a petition to request an annual subsidy from the city. But the councillors, possibly put off by Weber’s willingness to let the museum be used by students and intellectuals campaigning on left-wing issues in the spirit of 1968, refused the request.

Instead, they proposed buying the museum from her, paying the cost of her initial investment, then leasing it back to her rent-free, while contributing a small sum – a mere one-tenth of the annual amount requested by the patronage committee – to offset the running costs. “I refused the offer on the grounds that the suggested contribution – 30,000 Swiss francs per year – would not solve the financial problem of holding exhibitions,” Weber explains. To underline the museum’s international prestige, she informed them that “alternative bids by third parties – from Switzerland and other countries are being evaluated.”

With hindsight, it was unfortunate that these proposals went nowhere. If Weber, supported by her friendly committee, had been able to negotiate the running cost subsidy upwards to a realistic figure, its future could have been assured and the glaring and fundamental problem that has dogged the museum for so long – its failure to open its doors regularly to the public – might have been resolved sooner. Weber, however, as she had many times before and since, dug in her heels. The contribution the city had offered was not going to solve the museum’s financial problems. But even more than the sums involved, it was the stipulation about the museum’s activities that rankled: she would be allowed to continue to run the museum “provided the operation was not supported by circles that pursued goals or resorted to means that are inherently incompatible with the constitutional order of Switzerland.”

With this threat of political censorship, the possibility of a constructive dialogue came to an end. And for the next 15 years the stalemate between Weber and the city led to the worst possible result – the museum’s frequent closures. As the wasted years rolled by, the jocular suggestion by Max Frisch in 1971 that the museum be dismantled and offered for sale in the columns of the New York Times began to seem a more reasonable solution than the miserable status quo.

At this point the question arises – why was the city of Zurich unable to reach a compromise over a building that many other cities would have regarded as a major cultural asset, a way of enticing a regular flow of top-end tourists? The city was clearly aware of the problem: they tried four more times to persuade Weber to sell up. In the literature she has published about the saga, in particular her pamphlet entitled ‘An Explosive Story – The City of Zurich and Le Corbusier’s Last Building’, she paints herself as a lonely, embattled victim of philistine and predatory conservative politicians, fundamentally out of sympathy with her and her museum. And indeed the refusal of the authorities to do anything about the Haller Atelier, which blighted the museum’s opening and even today prevents visitors approaching it from an appropriate angle, suggests that no-one in authority fully understood the building’s importance. Yet it is hard to resist the conclusion that Weber’s own refusal to bend was part of the problem. Her steely determination had been vital in bringing the building to fruition, and her refusal to tolerate the slightest deviation from Le Corbusier’s intentions means that it remains a very faithful example of his work. But that same steeliness became an impediment once it was open.

As an insider (who asked not to be named) remarked: “With Mrs Weber, it’s always the same, for many years. The first contact is very good, but then when it comes to the details, her unhappiness grows… The museum is the work of a lifetime, it’s like her child.” Once the financial challenges of the museum became too much for her, the first priority should have been to do whatever was necessary to keep it open. Instead the indifference and parsimony of the city met the steely possessiveness of Heidi Weber, and no compromise was possible. The loser, for all these years, has been the general public. The long-running feud between Weber and the city of Zurich would be merely a shabby story of obstinacy and parochialism were the building not so good. But it is stunning. And that propels the story to another level.

The last building Le Corbusier designed is so light it practically dances, even in the dull light of the autumn afternoon on which I visit. It is remarkable that a man in his mid-seventies, not far from the end of his life, should have been capable of conceiving something so playful and so original.

In the museum we see the mature realization of many of Le Corbusier’s revolutionary ideas – but it also marks a fresh start. With its capricious inversions and zigzag angles, the steel roof seems as light as an origami paper sculpture. The main structure of the building, meanwhile, has the temporary, ad hoc look of a set of children’s building blocks. Formally speaking it is composed entirely of cubes, their slender steel frames enclosing big plate glass windows or enamelled steel plates coloured in the bright primary colours Le Corbusier favoured –“like a monumental Mondrian,” as Weber puts it.

The cubes are neatly aligned in rows two high, but there is little in the design to suggest that this is more than a temporary arrangement. The whole ensemble is less like a conventional building than an assembly of transparent modular shipping containers under a temporary canopy. All this was new – new in Le Corbusier’s work, and new in the thinking of modern architects. Most of Le Corbusier’s greatest works, from the Unité d’habitation in Marseille (1945) to the Ronchamp chapel (1950–5) and the posthumously completed Firminy church (1960–2006), are strikingly monumental, even sculptural, emphatically solid and permanent. The idea that a building could be not merely light in appearance – echoing Buckminster Fuller’s famous question, “how much does your building weigh?” – but also ephemeral, casual, contingent, temporary in appearance: this was new in his practice, even if it was implied by his famous description of a house as “a machine for living in”. This deliberately cultivated appearance of ephemerality and contingency was years ahead of its time. The avant-garde British architect Peter Cook’s revolutionary idea of a ‘plug-in city’, a framework into which dwellings could be slotted in then slotted out again, was still in the future, while Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Building in Tokyo, a development of that idea, would not be built until the 1970s. And here was the granddaddy of modernism doing it first, yet again. And it was not merely the look of it: all the main elements of La Maison d’Homme were indeed prefabricated in a factory, trucked to the site, then bolted together.

“There are 22,000 bolts in the building,” Weber informs me, with unfeigned glee. “It’s like Meccano, you know, it’s beautiful.” Max Frisch’s idea of unbolting everything and selling the dismantled building to the highest American bidder was not entirely fanciful. Charles Jencks, the eminent American architectural critic, is impressed by the vigour and freshness of the design. “Although it is the product of his old age, it’s very youthful in feeling,” he says, “partly because of Heidi Weber. And in its use of steel it anticipates by 10 years the high-tech that became the British standard mode for late modernism. It has stood the test of time remarkably well; and for a late work it is a little masterpiece … a stimulating kind of temple to art.”

Le Corbusier’s reputation has taken a hammering since his death because of the way his love affair with concrete inspired thousands of lesser architects to litter the world’s cities with high-rise horrors. But unlike his slavish followers, he himself was far more poetic than dogmatic in the way he designed: all his great works are full of contradictions. The use of steel was the most innovative aspect of the building, and it took Le Corbusier a long time and several changes of heart before he committed himself to it. His first plans, produced in December 1961, were for a building in concrete. Then he changed his mind and re-drew it in steel and glass, before once again returning to concrete.

“He said to me, let’s go back to concrete,” Weber recalls. “So I said, ‘Mr Le Corbusier, I very much like steel, because steel is the material of the future.’ So he said, ‘fine’ – but then he came back once again and said, ‘Mrs Weber, I am going back to concrete, because with concrete you can change and repair it. You don’t know what you risk with steel: if there is something wrong, you cannot replace it.’ So I said to him, ‘Mr Le Corbusier, I am very aware that I am risking everything with you. Let’s do it in steel’.” So steel it was.

For 50 years, Weber guided visitors around the museum with an enthusiasm which has never palled. The detail is so wonderful, she says: the bold colours Le Corbusier chose to distinguish the functional elements – bright yellow for the specially designed, square electrical sockets – “like a modern sculpture, they’re fantastic” – blue for the cold water pipes, red for the hot ones: the main hot water pipe, 50cm wide, travels from the rooftop tank right down to the basement, accompanying the staircase, and is an architectural feature in its own right, anticipating the exposure of functional elements by high-tech architects such as Richard Rogers.

There are the heavy wooden doors, curved like the doors of a ship, the immaculate and contemporary looking kitchen which, Weber says, has never once been used. There is what she calls “this marriage” of ramp and staircase, the only concrete elements. There is the craziest detail of the lot, a missing panel in the steel roof. “I said to him, ‘Don’t you think we should put a pane of glass here?’ He refused, he insisted on leaving it open – and when it rains, it’s a sensation.”

It is hard to connect Weber, now 90, with the rather fierce figure in the museum’s catalogues, her hair cut in a severe 1960s bob, sleekly elegant in the sleeveless shift dress the Parisian couturier Courrèges designed for her, standing vigilantly in the background while the bureaucrats and engineers and architects go to work on the Master’s plans. This is a woman who will not suffer traitors, her unsmiling expression suggests. Some of her collaborators couldn’t take it. “I don’t intend to be bossed about by a woman!” one of her architects declared in a fury as he stormed off.

That was a common sentiment 50 years ago. When the museum was inaugurated, Swiss women were still four years away from getting the vote. Even Le Corbusier himself was not immune from the sexism of the time. During one of their last meetings, he told Heidi that he had set up a foundation to look after his heritage. “I said, ‘Mr Le Corbusier, you gave me the contract to take care of your pictorial work for 30 years, I should be a member of this foundation.’ And he said, ‘No, I will have no women in it’. He was, after all, a man of the 19th century. Women were servants – there was no emancipation at all.”

Weber re-christened Le Corbusier’s La Maison d’Homme as the Heidi Weber Haus. For half a century she guided the museum, despite the challenges of running it with no financial support from the city, and despite what she interprets as a frosty, hostile, and sometimes even predatory attitude towards it and her on the part of a succession of city mayors. She might be forgiven for feeling a little jaded, but she denies it. “No, no. My great satisfaction is in the people who have visited the museum – at least two million of them, 50,000 per year, from all over the world. That’s what makes me happy, that is my work.” But that satisfaction, too, came to an end: her 50-year lease on the site expired in May 2014, and, evicted by the city, she lost control of the museum’s fate. What then? “It is thanks to Heidi Weber’s tenacity and total commitment that this iconic building came to exist in the first place and be located where it currently is,” observes art auctioneer Simon de Pury. “This building would be an invaluable addition for any institution focusing on art and architecture around the world.”

As far as the Zurich authorities are concerned, the many years of misunderstandings and bad feelings are water under the bridge – at least, that is how they would like it to be. When Corine Mauch was elected mayor of Zurich in May 2009 she wrote a letter to Weber acknowledging her work, the first such letter Weber had ever received. “I am aware,” Mauch wrote, “that you have not always received the estimation that you and your unremitting efforts would have deserved. I therefore consider it a matter of importance to enter into a dialogue with you.” The new mayor followed up this overture in the summer by paying a visit and presenting Weber with a bouquet. “She was the first office-holder to pay the museum a visit at the start of her time in office,” Weber notes. It was a good beginning, yet, most recently, Weber has sent an open letter to Mayor Corine Mauch of Zurich criticising the way the museum has been handled, and has also (unsuccessfully) tried to sue the city of Zurich. Nathan Bachtold, a spokesman for the mayor’s office, told me before the lease expired that they “would like to continue to have a museum there in the spirit of Le Corbusier and also in the spirit of Mrs Weber – to show the public what an asset we have in Zurich with the Le Corbusier house. We would like to establish a public foundation to run the building. One possibility is that Mrs Weber would have a place on the board… But after the discussions started we realized that there were different points of view. The main difference is that Mrs Weber would like us to donate the museum to her outright. But there would be no public interest in doing this, as the building will belong to the city.”

It would become a political issue, he warned. Weber’s camp, however, denies that she made such a request. “She proposed that the museum be donated to her existing Heidi Weber Foundation before the lease expires… and without payment of the 1 million-plus Swiss francs sum the city would have to pay her as indemnity,” her son Bernard told me. “This would in fact save public money. But for bureaucratic reasons the city sees a problem in co-operating with a private foundation, a mechanism which works perfectly well with other museums in Switzerland, such as the [Fondation] Beyeler museum in Basel.”

As the Pavillon Le Corbusier undergoes renovation until spring 2019, the saga of what might be Corbusier’s greatest legacy continues.

Photography by Greg White

A version of this story appeared in the winter 2013/2014 issue of Baku magazine.